#ChildGauge2018: Most child murders involve caregivers

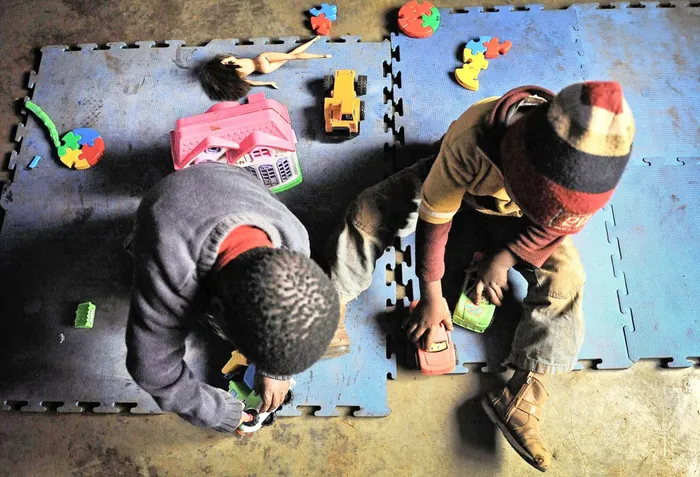

File picture: Dumisani Sibeko / African News Agency (ANA) File picture: Dumisani Sibeko / African News Agency (ANA)

Cape Town – Three in four murders of children aged 0-4 years old occur in the context of abuse by a caregiver at home.

This is according to the South African Child Gauge Survey released yesterday.

Now in its 13th year, the annual report is published by the Children’s Institute (CI); UCT in partnership with DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development; the University of the Witwatersrand; Unicef South Africa; and the Standard Bank Tutuwa Community Foundation.

Senior researcher at the CI and Child Gauge author Lucy Jamieson said although almost double the global rate, child murder was a relatively rare occurrence and children were much more likely to experience or witness physical punishment and domestic violence.

“The general definition for caregiver (in the study) is anyone that is actively looking after a child, including the parents.

“Part of it had to do with the vulnerability of children and also the changes that mothers go through in those early years. Most caregivers who kill children do not set out to kill children, it just happens in the context of physical abuse that can be fatal.

"The reality is that most children who experience physical violence experience it at the hands of women, normally the mother.”

The Birth to 20+ survey found that nearly half of preschool children were reported to have experienced physical punishment by parents or caregivers, and that physical punishment was often considered to be discipline.

Jamieson said the impact of physical punishment also resulted in long-term negative impacts for children.

“The first thing we are teaching children by using violence against them is to be violent.

"We have the research to see the long-term effects, and they range from increased aggression to learning difficulties, high stress levels and an impact on their employability.”

The survey also found that violence against women and children occurred in the same households and shared common risk factors.

Children’s Institute director Shanaaz Mathews said: “Our increase in knowledge on the intersections and links between violence against women and violence against children suggests that it is imperative for us to stop addressing the problem in silos but to start integrating prevention programmes to address both problems.”

She added that reporting rates for domestic violence were low as some women preferred to use traditional approaches “such as family meetings rather than the state legal systems because domestic violence is considered a private matter”.

The survey also focused on children at the interface of families and the state.

It looked at areas of effective collaboration as well as contestation or tension between families and the state, such as where families failed to nurture children in ways that the state requires, or when the state does not fulfil its obligation to provide an enabling environment in which to do so.

Lead editor of the 2018 issue Katherine Hall said that while families have increased access to services in the post-apartheid era, the government was urged to focus attention on improving the capacity and quality of responsive services to families.

“In general, the state recognises the diversity and multi-generational nature of many families, but in practice, different departments have divergent views of what a family is (or should be) and who is assumed to bear responsibility for children.”