South Africa’s democratic gains: Is the Constitution a gain or a barrier?

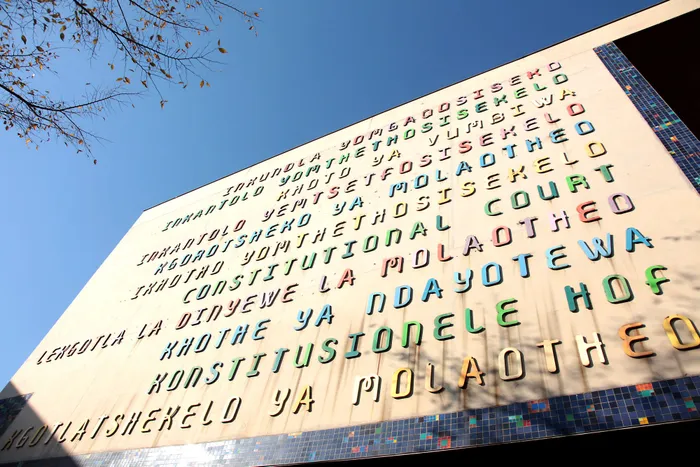

Constitution Hill is almost as old as the city of Johannesburg, and the story behind its historic museums is outlined in the pages on the Old Fort, the Women's Jail and Number Four. Picture: Nhlanhla Phillips/African News Agency (ANA) Archives

By Olwethu Mhaga

The promise and subsequent disillusionment, descriptive of South Africa’s democratic era personify Langston Hughes’ answer to the question posed in his famous poem “Harlem”.

He enquires “What happens to a dream deferred?”

And in conclusion resignedly answers “maybe it just sags like a heavy load, or does it explode?”.

The fundamentally unequal and stagnant economy has produced the “sea of black poverty” characteristic of South Africa’s landscape; as well as the deepening moral malaise manifested as institutionalised corruption and crime, which serve as compelling evidence of the deferral of the dream of a democratic South Africa in which all people live lives of dignity.

This ever-present failure to transform what is a fundamentally unjust society has led to an ever-increasing outpouring of anger, violence, rioting and looting. In response, many have begun questioning the very premises upon which our democratic constitutional order is founded.

Constitutional supremacy and the rule of law lie at the centre and have been the main targets of such attacks.

Sections of society now argue that it is the Constitution itself that has slowed or reversed the process of transforming South Africa.

This criticism is based on the argument that the Constitution is the product of crippling political compromises arising from negotiations during the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) and is further supplemented by an attack on the interpreters of the Constitution, being the Judiciary, arguing that African jurists sing from the hymn book of Roman-Dutch Law which has mentally colonised their mindset rendering them impediments of transformation.

Their subsequent answer to remedying these dilemmas presented by the system of Constitutional Supremacy lies in Parliamentary Supremacy. As seen in countries such as the United Kingdom, this is a system which ensures no other arm of government may undermine or invalidate the enactments of Parliament but rather tasks them with aiding in their implementation.

Parliamentary Supremacy characterised the South African Colonial and Apartheid eras' political philosophies.

It was last codified into South African law through the 1961 Constitution Act, which stipulated that “no court of law shall be competent to enquire into or to pronounce upon the validity of any Act passed by Parliament”.

Inevitably, however, the system culminated in the authoritarian tyranny that came to define both eras as innate fundamental rights that were subordinated to the pursuit of a racial caste society. If natural economic or social forces produced outcomes contrary to the stated aims of white supremacy then the answer was to oppress, repress, restrain, and constrain. The resultant price of economic inefficiency and loss of civil liberties in pursuit of the perpetuation of the settler-colonial state rendered the system doomed to failure, but these were nonetheless prices that politicians were always willing to pay.

Nevertheless, however effective colonialism and apartheid administrators were and regardless of their capacity for reform, the seeds of the system's demise lay in their fundamental misunderstanding of government and its relationship to the citizenry.

Rather than rights being granted by the government, people are born free and exercise their freedom to create a government that, at a minimum, secures those natural rights that pre-exist with the government.

Therefore, governments are instituted to secure pre-existing rights, not to bestow them, as was fatally mistaken by apartheid’s architects.

Certain rights and freedoms lie beyond the reach of the majority. Therefore, although governments derive their power from the consent of the majority, not all exercises of these powers, simply because they flow from the majority, are just.

A Constitution, as the law that governs those who govern, and the complementary principle of the rule of law is the most effective means of not only guaranteeing fundamental rights but also safeguards against majoritarian tyranny.

This creates a government strong enough to protect and enforce our rights but not strong enough to threaten them again. The proponents,

South Africa, of Parliamentary Supremacy, rightfully points out the system’s ability to effect change without impediment but fails to acknowledge the resultant abuse inevitable in its application, which has been the hallmark of pre-democratic South African life.

Political argument is often characterised by degree.

This is because the extent to which one goes in pursuit of goodwill is invariably affected by the fact that it may at some point come into conflict with another good.

The South African 1996 Constitution threads the tenuous needle-like balance between granting the necessary powers to enact transformative change yet safeguarding our pre-existing fundamental rights encapsulated in the Bill of Rights and should never be needlessly discarded.

A good example of this careful balance is Section 25 of the Constitution, dealing with property.

The section protects property owners from arbitrary deprivation of their property, yet nonetheless, considering the legacy and modern consequences of dispossession grants the government's wide-ranging powers of land redistribution and restitution.

The stipulated compensation is stated as simply being “just and equitable,” which may include no compensation considering the context of acquisition.

Further provisions implore the government to take all reasonable legislative steps and measures to effect land reform and equitable access to land.

By effectively crafting provisions that walk this careful tightrope South Africa’s founders achieved a monumental feat in piecing together the Constitution that would be difficult to replicate in a system of Parliamentary Supremacy.

Constitutional Supremacy and the rule of law are the centrepieces of South Africa’s democratic constitutional order and are the antithesis of the legal injustice which defined the past.

The failures which have come to pervade South Africa’s experiment with democracy will require unique and out of the box solutions, but to replace Constitutionalism would only serve to throw out the baby with the bathwater and render South Africa vulnerable to the wave of authoritarianism currently sweeping the world.

*Olwethu Mhaga is an admitted attorney and member of the ANC Youth League.