Oppenheimer film: These were the atrocities afflicted on Africans in search of uranium for the nuclear bomb

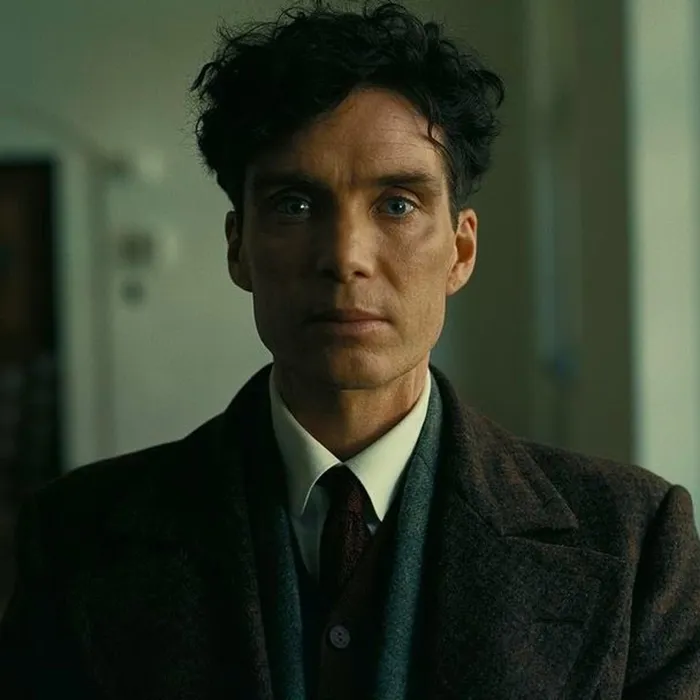

The movie has an ensemble cast including Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr, Matt Damon and more. Photo: Twitter

“I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds,” famously said J Robert Oppenheimer, quoting the Hindu scripture, Bhagavad Gita.

On July 16, 1945, the American theoretical physicist watched the first detonation of his design, a nuclear weapon and became horrified at its potential use in the world.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project (a US government nuclear research operation) and was responsible for the research and creation of an atomic weapon, earning him the title “father of the atomic bomb”.

This history is being brought to the silver screen by Christopher Nolan of “Interstellar” fame. Fans of the award-winning filmmaker are eagerly awaiting the release of “Oppenheimer” this July.

The movie has an ensemble cast including Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr, Matt Damon and more.

However, there is a dark history behind the creation of the nuclear bomb during World War II that is barely spoken about.

Nuclear weapons are made up of uranium or plutonium.

“Little Boy” was the first nuclear weapon dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, by the US and used uranium. But where did the scientists find this heavy metal?

According to the “BBC,” the majority of it was mined in Shinkolobwe in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but the country's part in developing the bombs that were detonated on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was kept hidden for decades.

The UK’s Dr Susan Williams, who wrote the book “Spies in the Congo: America's Atomic Mission in World War II,” was among the first to uncover one of the largest and darkest secrets of the 20th century.

“The word Shinkolobwe fills me with grief and sorrow ... It’s not a happy word; it’s one I associate with terrible grief and suffering,” she told the “BBC”.

To obtain the much-needed uranium, the Congolese were essentially forced to work in the perilous mines without any protection.

Uranium has the potential to induce a wide range of negative health impacts, including renal failure and decreased bone formation, as well as DNA damage. Low-level radiation causes cancer, shortens life, and causes minor changes in fertility.

The central African nation was under Belgian colonial rule at the time and the mine workers were virtually slaves to the Belgium mining company, Union Meniere du Haut Katanga.

“Production at the mine would continue throughout the war, using Congolese workers to do the secret, dirty, dangerous and radiation-steeped work. Several hundred tons of uranium were shipped monthly to the various Manhattan Project sites,” said the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

No research has been conducted on the long-term consequences of uranium intake in people at the extraction location in the Congo.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology said that dust from the sites and the water used for dust management include long-lived radioisotopes (unstable forms of a chemical element that releases radiation as it breaks down and becomes more stable) that migrate into the surrounding areas.

Additionally, low radioactive effects might take decades or generations to manifest and are not detectable in short-term toxicity investigations.

“In the atmosphere, radon decays into the radioactive solids polonium, bismuth, and lead, which enter water, crops, trees, soil, and animals, including humans.

“The Congo’s total tragedy due to WWII will never be known. The effects of the war on the Congolese people are still being felt to this day. Nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation will be the best remedy to avoid this suffering from ever happening again,” it said.

IOL News