Suffering to make the world better

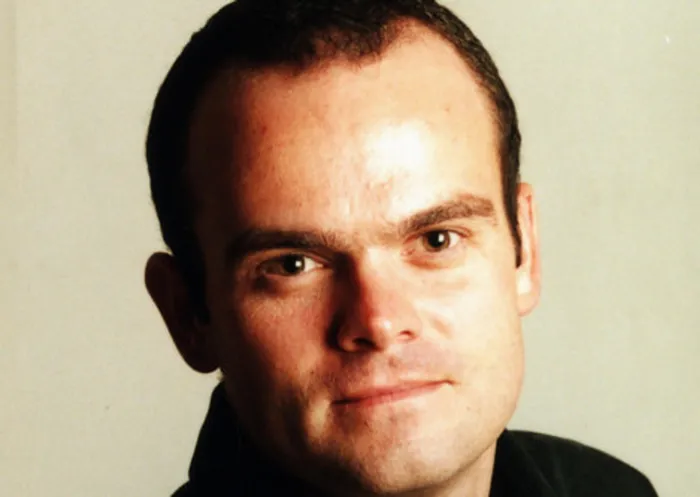

Independent Media's Chief Sports Writer Kevin McCallum Independent Media's Chief Sports Writer Kevin McCallum

The road to the Grand Bassin in Mauritius is steep and winding. It may just be one of the most beautiful climbs I have cycled on. Last week Monday it was also one of the most beautiful climbs I have held on to a car on. I felt shame, I felt a sense of surrender and I felt relief. An incline of 15-20 percent is no place for soft legs, and mine, which had been soft coming into the Change a Life Wonderland Tour, were a little harder but tender after 400km over the previous three days.

The Change a Life Tour went to Mauritius for its ninth year to celebrate almost a decade of raising funds for grassroots initiatives with the aim of providing a “peaceful future” for South Africans. It’s a lofty goal, but with millions of rands raised and invested, and awareness heightened, it’s a lofty aim with a solid base that does its bit to help social change. To do this, they invite around 70 of the country’s top executives to ride bicycles, suffer a little or a lot and to pay for the privilege. The road to social cohesion and the uplifting of the lives of others is steep and winding and hard, and can be the most beautiful thing you can do as a human.

Martin Dreyer needs no introduction. He is the Jonny Clegg lookalike Dusi king. He began the Change a Life Academy in the Valley of a Thousand Hills eight years ago to help realise the massive athletic potential he saw in kids who ran alongside him in the Dusi on the banks of the river. Paddlers from the academy were represented in 10 of the top 26 crews at this year’s Dusi.

The academy won the Foundation Award for their work at the World Paddle Awards in Barcelona this year. He has begun a schools running league and a mountain bike team. John Ntuli won the 1070km Munga mountain bike race from Bloem to Wellington this year.

In Mauritius, Dreyer pushed those of us who had neither the talent nor the training of Ntuli. Like he has done with his charges at the academy, he wanted to show us how to stretch our limits a little bit more, to give them some small insight into who and what he is.

I had Robbie Hunter as my roommate and back-up on the road in the White Rabbits team. I have enough muscle memory to ride on the flats and over rolling hills. On the bigger bumps, Hunter’s hand on the small of my back came as welcome relief. They call it the hand of shame, but when the road went up, I had little shame.

The participants on the Change a Life tour have become a family. There is a waiting list a mile long to get on to the Tour. Those who have their spots guard them carefully and very few give up the chance to take part.

We rode Pinarello Dogma F8 bicycles, the same bike Chris Froome won the Tour de France on this year. They cost more than I paid for my first house. We could buy the bikes for a good discount after the tour if we so desired. But they did not offer the same discount to me for a smaller bike as they did to Derek Watts, who was on the Tour on a steed that looked like a farm gate. His bike uses more carbon than mine. Surely, then, you would think, it should be cheaper. Was it a good bike? It was a great bike, whisper smooth and fast, so damn fast.

The Mickey-taking is legendary, the jokes do not stop. None are safe, not the CEO of the JSE, the chairmans of boards, the CEOs of companies who manage billions in wealth. Egos are not tolerated, laughs, hugs and encouraging words mandatory. I was called “Midget” from the first day by one Adrian Nunn, the joker of the Tour.

On that last day on the climb to the Grand Bassin, as the road headed up, I slipped back to catch a drag on the bakkie. “Hey, midget! Welcome.” shouted Nunn across at me as he held on to the left-hand side. It was a long and steep and tough climb. It was also perhaps the most fun I have had on a sports tour.

The Star