Fiela's child lives on in Knysna Forest

A small memorial in the Knysna Forest, just off South Africa's famed Garden Route, pays tribute to Dalene Matthee, the award-winning author whose books have done so much to place the region firmly on the international tourist route.

The sub-tropical forest, with its giant stinkwoods, yellowwoods and ironwoods, is marked by deep ravines covered in dense bush. It's a place of incredible beauty, criss-crossed by streams, and home to a range of creatures, including elephant, antelope, monkeys and birds. Intriguingly, it has a gold mining history older than Johannesburg's but, for all that, it is Matthee's books that lure visitors here.

Fiela's Child, perhaps her best known novel, tells the story of a little white boy who wanders deep into the forest and disappears. Nine years later, on the other side of the mountains in the Long Kloof, government officials find a white child living with a coloured woman, Fiela. Benjamin Komoetie is forcibly returned to poor white woodcutters in the Knysna Forest whom, they say, are his family.

Another of Matthee's books, Circles in a Forest, tells of the extermination of the Knysna elephants, another tale of haunting sadness.

Books, like many films, have become valuable tools for tourism. Readers are ever ready to travel far to experience the settings used by popular authors, be they Bill Bryson's travel tales or J K Rowling's Harry Potter adventures.

When we visited the Knysna forest recently, we joined groups of other visitors who had come to walk in the woods and picnic under the tall trees.

Among them was Maud Abercrombie who explained that her family had planned a holiday to South Africa because she wanted to see the Knysna forest.

"Fiela's Child has haunted me ever since I read the book some years ago," she said.

"I had to come and see for myself. I wanted to see where Benjamin lived and where he was taken when they removed him from his mother."

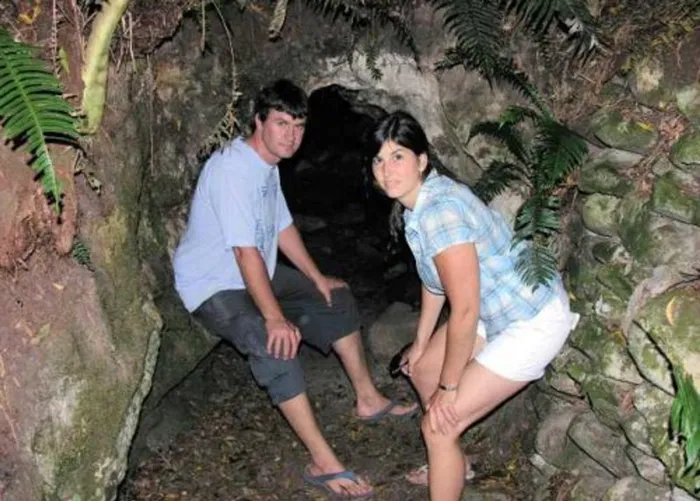

Matthee's story had much the same impact on us as we walked through the trees, following a trail along the Houtini River. We stopped to watch a group of little boys swimming under a bridge and could almost see the children of yesteryear's woodcutters among them. Higher up, we encountered young people swimming in a forest pool and showering under a waterfall.

The Knysna forest has been exploited for its timber since the 1700s when woodcutters - mainly poor Afrikaners - moved into the area and started felling the trees, turning the timber into planks for furniture, building construction and shipbuilding. Areas were cleared for crops and cattle farming.

All that changed in 1939 when the government, in response to the destruction of the

forest, stopped the exploitation. The forest was reopened 36 years later for use by the state under the control of forestry scientists. At the same time, owners of private forests in the area did their bit to rehabilitate patches destroyed by man. Today only managed harvesting is allowed.

Try as we did, we could find no sign of the famous Knysna elephants. In the 18th and 19th century they roamed the coastal plain, eventually moving into the forests to escape hunters.

In 1867, when Queen Victoria's son, Prince Alfred, visited South Africa, he sailed from Cape Town to Knysna to hunt elephant. Then there were about 500 "bigfeet" in the forest. By 1920 just 12 remained and by 1990 four. Recently someone claimed there were still a couple in the forest.

But if the absence of elephants was a disappointment, the massive trees were certainly worth seeing, particularly the various yellowwood and stinkwood, the Cape beech, Cape holly and red alder. Certain specimens are marked for visitors.

We had all hoped that we might see some of the mammals of the forest, which is home to blue duiker, bushbuck, bushpig, leopard and baboon.

Once we thought we'd spotted a samango monkey high in a tree, but it disappeared even before we could train our binoculars on him.

Our only sightings were a flash of a boomslang, a wood owl and a minute tree frog.

Later, as we left, we spotted a colourful Knysna loerie.

Wading upstream, we encountered evidence of early gold mining. There was something of a gold rush in the forest before gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand.

A farmer collecting grit for his ostriches in the Karatara River, found a stone that he thought had traces of gold in it.

At the time, a man named Charles Osborne was working with the famous road builder Thomas Bain who was building a road through the forest to connect George and Knysna.

Excited by the find, Osborne returned in 1886, no doubt determined to make his fortune. It was a heady time, with hundreds of men emerging from nowhere to pan for gold, sieve through the gravel and dig tunnels in search of riches.

A village was created and a couple of hundred wood and iron houses built in the forest. A number of hotels and boarding houses went up, as did a hospital and church. Cricket matches were arranged between Knysna and the new village of Millwood and a postal service was even introduced. For a short time life was good, but few found the treasure they sought.

Then gold was discovered in Johannesburg. By 1890 companies that had invested in the forest had ran out of money. A decade later the place was deserted - except for the rusting remnants of mining equipment. Years later the authorities had to haul out machines from underground workings.

As we peered into tunnels and let the gravel in the streams wash through our fingers, I couldn't help thinking it was a blessing that no gold had been found. What would have become of South Africa's largest forest had those enthusiastic miners struck it rich?

Our excursion into the forest took place on a warm, wind-free day. Weary after our hike, we headed for the tearoom in the ghost village of Millwood.

Nearby was Millwood House, part of the Knysna museum complex which contains items of historical interest. We, however, were satisfied.

Dalene Matthee may have died five years ago, but through her legacy we had found the spirit of the forest among the trees.

- For more information and accommodation in the area, visit Visit Knysna.