Kings of the shifting sand

It's our last day and still no desert lions.

Our guide, Chris Bakkes, has been following fresh spoor for a while now - the lions must be close.

Suddenly, a roar from the tamarisk trees (Tamarix usneoides) breaks the silence. We drive through a dip and there he is, a magnificent male, golden mane catching the early morning rays. Two females slide out of the bush behind him, then three inquisitive cubs bound towards our vehicle.

We sit enthralled, watching the desert lions playing in the riverbed.

On the trail of desert rhinos

Getaway publisher Jacqueline Lahoud and I had stepped off a Cessna at Desert Rhino Camp in Damaraland. Behind the dust of the propeller emerged Chris and led us to a waiting Land Rover.

Rhino Camp is run as a joint venture between Wilderness Safaris and Save the Rhino Trust.

Desert-adapted black rhinos have survived in this harsh landscape and miraculously escape extinction through poaching.

They live off the meagre vegetation the desert offers.

After 11 hours of non-stop tracking, we happened on a young bull asleep in the shade of a euphorbia.

But the wind shifted and he caught the scent of our vehicles.

The rhino was up in a flash, head and tail raised, ears twitching. Then he glided off on dainty legs and was swallowed by the desert.

Into the wild

Next day, we left the basalt heights of the Etendeka Mountains, crossed grasslands dotted with welwitschias, traversed gravel plains and dropped through granite schist kloofs to the bed of the dry Hoanib River.

Hartmann's mountain zebra cantered beside us; meerkats poked their noses inquisitively in the air; kudu stood dead still.

The birding was also good.

Benguela long-billed larks whistled from the tall grass, black-chested snake-eagles, auger buzzards and gabar goshawks drifted by on the thermals, Ludwig's bustards lumbered into the air and Namaqua sandgrouse called their kelkiewyn chant on the wing.

We reached Hoanib Camp, a cluster of tents in a kloof overlooking the river bed.

At sunset we climbed a koppie.

Below us gemsbok jousted, a herd of springbok pronked and a herd of giraffe ambled "upstream".

In the morning, we went looking for elephants.

Everywhere we saw evidence - dung and pad prints, ana trees (Faidherbia albida) neatly pruned at exactly six metres and holes dug in the riverbed. It didn't take long to find them - a small herd munching on a stand of camelthorns.

These are very special elephants. To survive in such a dry environment, desert pachyderms range widely, travelling up to 60km a day between springs.

A shoreline of wrecks

Next, we based ourselves at Skeleton Coast Camp, the only lodge in the Skeleton Coast Park.

From there, we explored the shoreline as far as Cape Frio in the north and the mouth of the Hoarusib River in the south.

The stark landscape changed from dune fields, salt pans and mountains seamed with agate, to a shore frequented by 50 000 Cape fur seals.

It was breeding and mating season and there was noisy pandemonium. Scavengers hung around, ready to pick off the weaker pups.

We witnessed jackals drag a baby on to a ridge and tear it to shreds.

Nearby, lappet-faced vultures were doing the same.

The dunes were like charnel houses, strewn with the bones, pelts and flippers of seals, with the smell to match.

Further south, we came on the first evidence - a lonely grave on the beach - of the Dunedin Star's famous wreck. For hundreds of years, the Skeleton Coast has been a graveyard of ships.

The Dunedin Star was one such victim. She was an armed cargo liner on her way to Egypt in 1942, carrying war supplies.

The vessel struck a shoal and her captain ran her aground north of Cape Frio.

In a legendary rescue operation, search ships were unable to take survivors off the beach.

An aircraft was sent to drop provisions and two vehicle convoys were dispatched in an overland rescue attempt.

On her way back to Walvis Bay, one of the rescue ships, a tug called Sir Charles Elliott, ran aground near Rocky Point. The grave commemorates the loss of two crew members who drowned.

The rescue plane tried to land on the beach, but became bogged down. The overland expeditions rescued the survivors of both ships and the airmen.

Members of a third overland mission managed to dig out the Lockheed Ventura bomber.

Captain Immins Naudé and two crew took off.

But 45 minutes into the flight, an engine seized and the plane nosedived into the sea near the mouth of the Hoarusib.

Fortunately, it drifted ashore.

As the captain's ankle was broken, he dispatched an airman overland to a spring where he knew the returning convoy would stop for water. The airman made it just in time.

People of the desert

"Archaeologists think these are Strandloper shelters," said Chris, standing beside a ring of stones.

The Strandlopers lived off what they could scavenge on the beaches and fished. We found white-mussel-shell middens and the remains of stone tools, evidence of habitation that lasted well into the 20th century.

Further inland was a more complicated set of circles, constructed in lines across a narrowing gorge.

"My theory is that this was a hunting trap," said Chris.

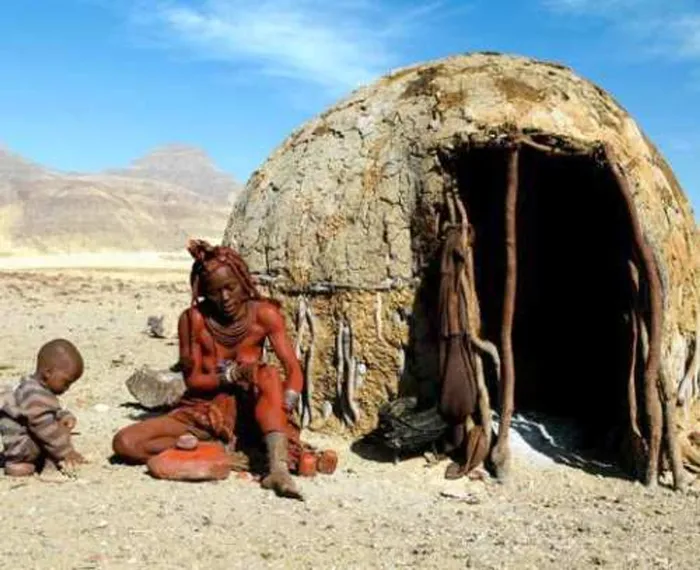

We pulled up at the Himba kraal of Chris's old mate, Kama-thitu Chipombu.

Daily clan life unfurled around us - goats were led out to pasture, cows milked, children ate their breakfast from a potjie.

These proud, nomadic people have remained relatively cut off from the effects of Western society and still practise a pastoral existence.

Castles made of clay

From our camp, we explored the Khumib and Hoarusib. The latter is a mighty river by Namib standards and floods every year.

Emerging from the Etendeka Mountains, it passes through two spectacular gorges - Kleinpoort and Grootpoort.

The terrain changes from basalt hills to crumbly schist to granite boulders and finally dunes.

The colours bleed from pink feldspar and red garnet sand to rocks stained orange with lichen.

An interesting feature of the Hoarusib is a series of curious formations known as clay castles. Many millennia ago, dunes blocked the mouth and the river silted up. At some stage, the water broke through to the sea again.

Getaway Guide

Getaway flew with Air Namibia to Windhoek. There are daily flights at about R4 000 return. Call + 264 61 299 6333, or see www.airnamibia.com.na

Where to stay

Wilderness Safaris has six camps in the Kaokoveld: Doro !Nawas, Damaraland, Serra Cafema, Desert Rhino, Hoanib River Camp and Skeleton Coast.

Getaway visited the latter three - all beautifully sited with safari-style luxury tents and en suite bathrooms.

Rates range from R1 430 to R7 195 a person a day. Call + 264 61 274 500, or see www.wilderness-safaris.com

Overlanding

Wilderness Safaris offers guided overland tours in stretch Land Rovers, stopping at lodges and camps, notably Hoanib.

Options include Desert Rhino and Elephant Expedition (seven nights) and Spirit of the Namib (nine nights).

Prices range from R3 208 to R7 345 a person and include all meals, a guide and vehicle, entrance fees and activities. Contact Wilderness Safaris.

The Kaokoveld is a harsh environment for the self-drive overlander (we saw only four other vehicles in a week). Come well prepared and be wary of flash floods in summer.

Remember, the Skeleton Coast Park is strictly out of bounds (the fines are heavy).

A popular option is to explore the area administered by Wilderness Safaris to the west of Palmwag.

You need to buy a permit at Palmwag (many people overnight at the lodge, which has chalets, luxury tents, a campsite and game drives, walks and cultural visits), then follow the Western Touring Route, either camping at the designated spots or booking into Hoanib River Camp. For permits (R70 a vehicle, plus R40 a person a day) and bookings, contact Wilderness Safaris or Palmwag Lodge. Tel + 264 61 274 500, or see www.widerness-safaris.com

- Published by arrangement with Getaway magazine. For the full story, see the February edition.