South Korean kids start English early for college success

early education

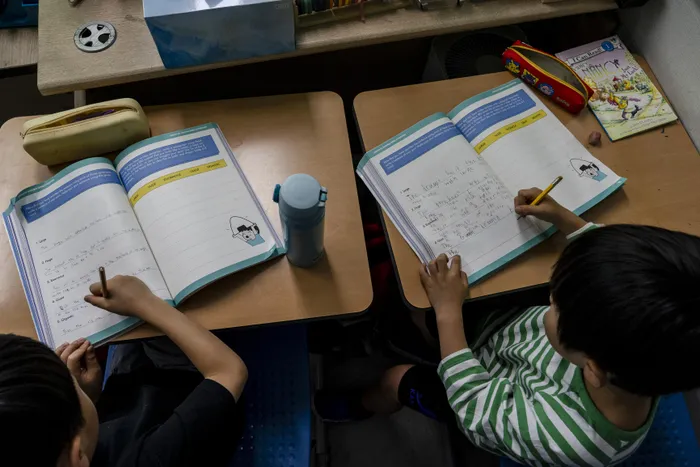

Starting their education early at a school in Seoul.

Image: Supplied.

THE South Korean kindergartners squirmed through their English-language writing class. They were not doing their ABCs. They were getting a head start on a defining moment more than a decade in the future: their college entrance exam.

“Write a paragraph of five to eight sentences using five synonyms for large,” said Ms. Keri, their teacher. The kids began jotting down ideas in neat handwriting.

But their minds wandered easily. “Make a stinky paragraph!” one girl yelled in English. The class erupted into uproarious giggles, echoing: “Stinky! Stinky!”

South Korea has long been notorious for its hothouse education system, where kids go from classes at middle or high school straight to after-hours tutoring at cram schools, often until 10 or 11 p.m.

These private programs prepare students for extremely difficult college entrance exams. Getting into an elite university is often seen as the golden ticket to a stable career at a top-tier company or government ministry.

But the race to the top schools is intensifying amid a widening income gap, fueling parents’ anxieties about their children’s future job security, experts say.

As a result, some parents think it’s never too early to start preparing for college. Nearly half of children under 6 are now receiving some type of private education, most commonly English classes, according to a government survey released in March.

“The opportunities to succeed keep dwindling, but there is one rare path that remains available, which is going to a good university,” said Won-pyo Hong, a professor of education at Yonsei University in Seoul.

The 6-year-olds learning from Ms. Keri - Keri Schnabel, a 31-year-old from Rhode Island - are among a growing cohort of South Korean children who are enrolled in private early-education programs. Such programs are almost always focused on developing English fluency - a must-have for social mobility and a marker of intellect and wealth.

Some curriculums claim to teach math skills so advanced the kindergartners would be on track for medical school. There are even classes that train toddlers to sit without fidgeting for up to an hour at a time to build study habits early.

These niche programs have become increasingly popular in the most affluent areas of Seoul, where some families shell out upward of $1,400 (R26 000) for the classes and related fees every month.

The skyrocketing cost of giving a child the best shot in life is one of the reasons South Korea has the world’s lowest fertility rate and is facing a demographic crisis. Government surveys show the rising cost of private education is one of the factors deterring couples from having more than one child or starting a family at all.

Gaining an advantage

These early-childhood English classes are usually taught by native English speakers, like Schnabel, who teaches at Twinkle English Academy in the affluent Seoul neighborhood of Mokdong.

The 5- and 6-year-olds in her class learn about idioms, similes and parts of speech from U.S. textbooks, including one for American second-graders.

They speak in fluent English to each other and their teacher - sometimes about “eating lava,” sometimes describing black holes as a “giant singularity.”

By the end of this program, they will write two-page essays with an introduction, three body paragraphs and a conclusion - the skill level of an American third-grader.

“The point of the English kindergarten is to do well in the next level, which is in elementary school,” said Kim Hye-jin, 37, whose 5-year-old attends English classes in Daechi, where private educational institutions are concentrated, in the ritzy Gangnam district.

Those places have long wait lists for prospective first-graders, who are required to take entrance exams. A recent documentary by the broadcaster KBS found some of the entrance tests are at the English and math level of high school freshmen. Prep schools pepper social media with advertisements claiming high success rates, and there is even a black market for entrance exams to help kids study.

The Education Ministry last month launched an investigation into these marketing practices and extreme prep programs.

An ‘unavoidable’ system

In Daechi, buildings are lined with signs for an assortment of “study cafes” and cram schools - English, math, coding, debating and more. There are even rest areas for students to take a breather between classes, including a “screaming zone” where they can vent.

More psychiatric and alternative medicine clinics are cropping up in the Gangnam area, according to domestic media reports. The number of health insurance claims for depression and anxiety among children 8 and under in the area has more than tripled in the past five years, according to figures released in April by the education committee in South Korea’s legislature.

Seo Dong-ju, 41, whose 5-year-old attends a less intensive English school in the Gangnam area, is not convinced that a competitive cram-school path is the right one for his son.

“My kid still loves dinosaurs and animals, so much that we always take him to the aquarium,” said Seo, a thoracic surgeon.

Seo said he is concerned about the long-term physical, psychological and societal impacts of excessive schooling on little children.