Medieval England’s murder hot spots revealed in new ‘killer map’

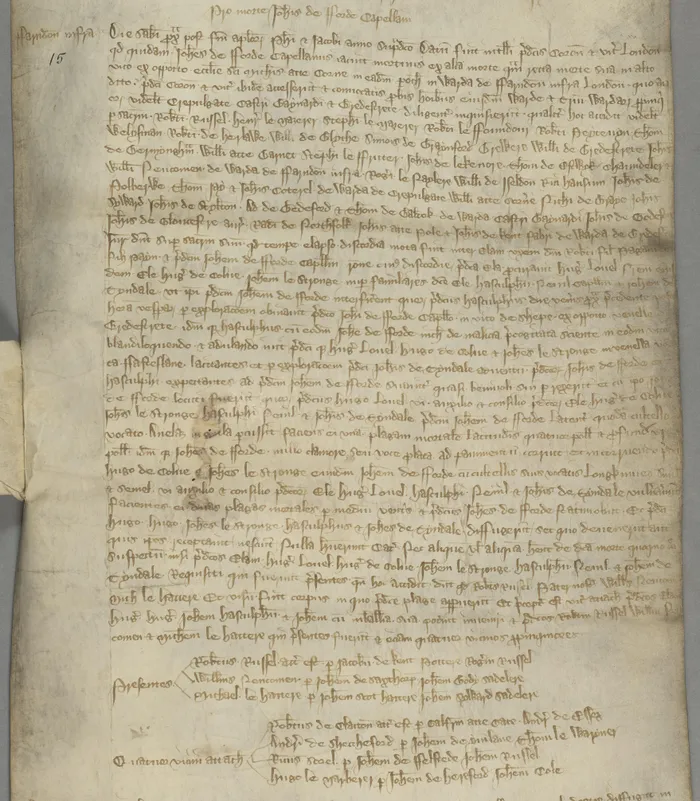

The original coroner’s report on priest John Ford’s death.

Image: London Archives/University of Cambridge

A saddlemaker ambushed outside a brewhouse. A man stabbed to death after he stumbled over a heap of dung while trying to flee a fight. And a priest killed by three knife-wielding assailants, possibly on the orders of a noblewoman accused of having an affair with him.

Each of these attacks took place at the same violent “hot spot” in medieval London, and they were among more than 350 homicides committed across three English cities that have been chronicled in extraordinary detail by a small team of academics and enthusiasts.

Using 14th-century coroner’s rolls and other archival sources, Manuel Eisner, a criminologist at the University of Cambridge, has spent 15 years working on interactive tools he calls “murder maps” with the help of a team including his wife and daughter.

“Each of these stories shines a little spotlight on an event in some corner of London,” Eisner said in a phone interview this week.

Taken together and analyzed in a peer-reviewed paper published last week, their findings offer a glimpse into the dark underbelly of medieval life in London, Oxford and York. They also reveal some trends that may surprise modern readers: Some of the deadliest hot spots were in the most affluent areas, and male college students were among the most frequent killers. The authors also found that slayings tended to cluster in high-footfall outdoor areas and that the majority of killers enjoyed impunity.

“Homicide was much more frequent than it is in modern times,” Eisner said. The deadliest of the cities was Oxford, which he estimated to have a homicide rate of about 100 per 100,000 inhabitants in the 14th century, while London and York hovered at 20 to 25 per 100,000. (In 2023, the most recent year for which data is available, London’s homicide rate was about 1.2 per 100,000 inhabitants.)

Oxford’s “spectacularly high” homicide rate was partly because it was home to so many college students, who made up the majority of both victims and suspected killers, Eisner said.

The students were mostly teenage men and boys, far from home, who frequently engaged in gang-like fights with one another and with townspeople. The details of how they met their untimely ends are varied: In one case, a mob of students rampaged through the city with bows and arrows. In another, a student was mistakenly killed after he stepped out in the middle of the night to urinate, becoming caught between two warring gangs of students.

Hannah Skoda, a historian at the University of Oxford, uses the map to teach medieval history to contemporary Oxford undergraduates (who are far less bloodthirsty than their predecessors). “Thinking about space really gives us a different perspective on what’s going on,” she said in a phone interview.

As she looked at the map of Oxford with some of her students during a lesson in her office, the group’s attention was drawn to one pinpoint in particular, she said. “A murder had taken place literally right outside my window in the 14th century!”

By mapping the homicides, Skoda says, it’s possible to physically explore the locations and picture the scene of the crime: Who might have seen the attack? Was it a premeditated ambush, or a sudden outburst of violence?

Poorer neighbourhoods were not associated with higher rates of homicide, the study said, “contrary to findings in modern societies.”

In London, for instance, the most prominent homicide hot spot was Westcheap, which Eisner described as the medieval equivalent of New York’s Fifth Avenue. “It’s the widest street in London, it has the tallest buildings on both sides, it’s the location of all the upscale markets,” said Eisner, adding: “I would not have expected a concentration of assassinations in these prestigious, highly visible places.”

Eisner and his team mapped over 20 killings on Westcheap’s 500-yard-long street and its offshoots, including one of the highest-profile attacks - the 1337 murder of John Ford, a priest who was set upon by a knife-wielding gang in broad daylight.

A jurors’ report from the time noted that Ford had been involved in a long-running dispute with the sister of one of his assailants, a noblewoman named Ela Fitzpayne.

However, her possible motive remained a mystery to historians until Eisner found further documents as part of his project. Some years before the murder, the archbishop of Canterbury had denounced Fitzpayne, accusing her of having a sexual affair with Ford, and she was ordered to walk barefoot along the length of Salisbury Cathedral carrying a four-pound candle once a year for seven years as punishment.

This suggested the attack on Ford could have been “a revenge killing by a powerful woman against somebody who’s probably caused her a lot of problems,” Eisner said.

The murder “could have been a soap opera plot,” said Matt Lewis, who hosts “Gone Medieval,” a history podcast. “You’ve got the sex, the intrigue, the divided loyalties and violence, and the message that’s being sent by doing it in public.”

The medieval era is also on the cusp of when detailed official records of events became available, so it was ripe for intrigue and investigation, Lewis said. “It makes it a great place to go mining for these stories.”

According to the research, over 90 percent of recorded homicide victims and suspected killers in all three cities were men - although Eisner cautioned that domestic violence against women and children may have gone underreported.

The research also shines a light on medieval England’s criminal justice process. After a killing, passersby were obliged by law to raise a hue and cry out for help. A coroner would then summon an investigative jury that would identify a suspect - although only 23 percent of recorded homicide cases resulted in an arrest, according to the research.

“Conviction rates were not only very low because people ran away, but also they were quite low because at that time many people were of the understanding that if you were attacked by somebody, you had to fight back,” Eisner said. In many cases, the jury would determine that the killer was acting in self-defense.

Unlike those accused of crimes such as theft, suspected killers came from across the social spectrum - including the elite, Eisner said. That provided another motivation, Eisner suggested, for a jury to return an acquittal.

In the murder of Ford, for example, Ela Fitzpayne was never tried, and only one person - one of her servants - was eventually convicted, Eisner said.

“Some of the things that aristocrats and the well-off get up to in this period are completely terrifying,” said Skoda, the Oxford historian. “Violence is seen as a way of dealing with things right across the social spectrum.”

People would have found the public killings terrifying, Skoda said, adding that that would explain why so many of the crimes - including Ford’s killing - were committed in busy thoroughfares.

“It’s clearly intended to be spectacular and to terrify and humiliate in a public sense,” Skoda said.