Journalist Karin Mitchell has authored The High Treason Club, which delves into the Boeremag trial of a fanatical group driven by nationalism, racism, militancy and fear.

Image: Hamish Mitchell

On the night of 30 October 2002, eight bomb blasts tore through Soweto, leaving one woman dead and damaging vital infrastructure. The bombs were the work of far-right white Afrikaner separatist group the Boeremag, whose stated aim was to overthrow the ruling ANC government, rid the country of black people and reinstate a new Boer-administered republic.

After a cross-country manhunt, 23 men were arrested and charged with high treason after the police seized explosives, homemade pipe bombs, weapons and ammunition in arms caches all over the country.

In what became the longest and most expensive trial in the country’s history, told in reporter Karin Mitchell’s book The High Treason Club, the public learned of a fanatical group driven by nationalism, racism, militancy and fear.

Mitchell also covered the Marikana Massacre, the Oscar Pistorius trial and other significant political events. She has been writing full time since 2016.

This is an edited extract of The High Treason Club published by Penguin Random House at a suggested retail price of R340.

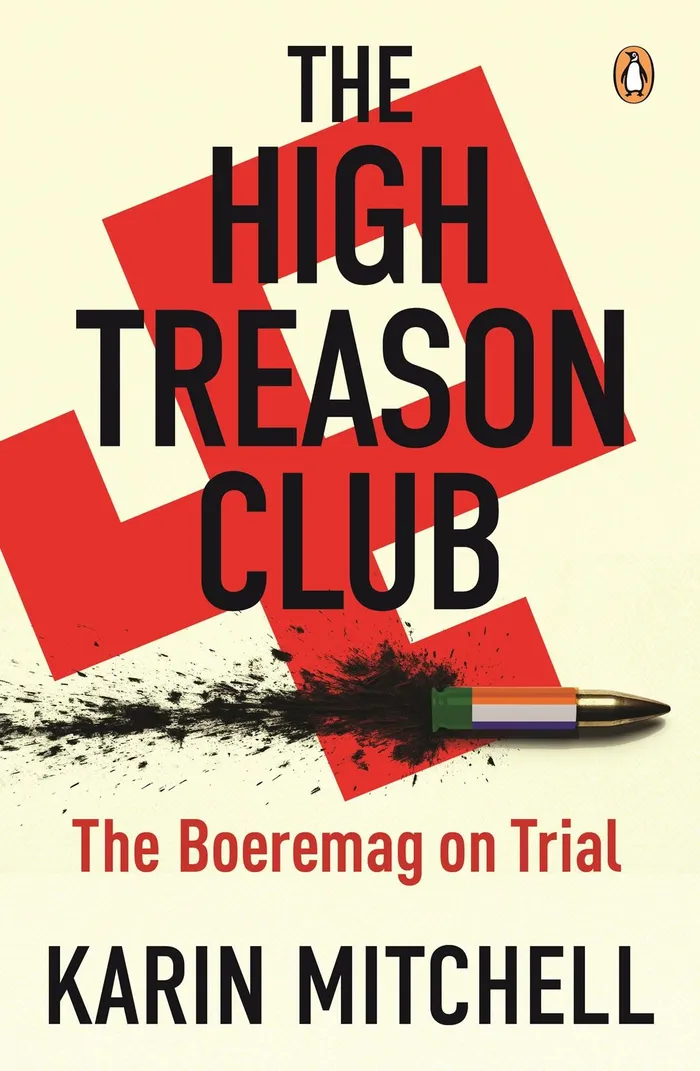

The cover of Karin Mitchell's book The High Treason Club.

Image: Supplied

Treason

It was 19 May 2003, the first day of the Boeremag treason trial. The early days of the trial were held in the Palace of Justice in Pretoria, ironically in the same courtroom where Nelson Mandela was sentenced in the pivotal Rivonia treason trial in 1964. At that time, capital punishment was in effect, and it was almost certain that Mandela and his co-accused would be executed in the Pretoria gallows if they were found guilty of some of the 200-odd charges against them.

Almost 40 years later, the Boeremag accused sat squashed against each other in the same dock where Mandela delivered his famous speech in which, fully aware that he could be sentenced to death, he vowed he was prepared to die for the liberation of black people. The court found Mandela guilty on four charges relating to sabotage against the state.

He was not sentenced to death, as had been widely expected, but was instead sentenced to life in prison. He spent many of the next 27 years excavating rock in the dusty white quarries on Robben Island, within sight of Cape Town and the South African mainland.

Four decades after Rivonia, the trial of the Boeremag became the first high treason case to be heard in democratic South Africa. After some months, the trial was relocated and the remaining twenty-two accused lined the weighty double-rowed dock in a larger courtroom at the North Gauteng High Court, just across the road from the Palace of Justice.

It was here that I first encountered the Boeremag eight years later, in May 2011, as a fledgling journalist for Jacaranda FM.

Time drags in court, and on days when it felt particularly stagnant, I would observe each of the men. They’d already spent close to ten years in this courtroom, and over time I became aware of some of their habits to overcome the boredom. Some of them read outdoor magazines or a newspaper would get passed along the line until the pages became worn. Others wrote in notebooks or sketched on pieces of paper.

I was often the only journalist in court for weeks on end during the period that I covered the trial. Taking advantage of the empty public gallery, I would sit at the end of the front row where it was easier to hear proceedings in the cavernous space.

I had been reporting on the trial for over a year when, on 26 July 2012, in an unusually packed courtroom, Mike du Toit became the first of the Boeremag accused to be found guilty of high treason. Since there were more than twenty accused in the trial, the judgment proceedings spanned several days. The following day, his brother, André Tibert du Toit, was also found guilty.

On that day, after Judge Eben Jordaan had left the courtroom, I rushed over to the dock to get a comment from either Mike or André. I wanted to capture their reactions to being convicted. As I was making my way towards them, Mike stood up, shook his brother’s hand, laughed and said, “Welcome to the High Treason Club!”

His comment stopped me in my tracks, and I knew that I’d just witnessed something momentous. I was incredibly disappointed that I had not been quick enough to record the exchange between the brothers, as it perfectly encapsulated the comradery that had grown between some of these men over the decade that they had been on trial.

Although I’d been attending the court proceedings since the previous year, I’d pretty much kept to myself, popping out into the foyer to report for our hourly radio news bulletins, not really interacting with anyone. So, I had to literally force myself to go up to the man regarded as the “Boeremag kingpin”.

“Excuse me, sir,” I said with polite hesitation. “Could I please ask you to repeat what you just said to your brother so that I can record the moment?”

Mike looked at me and the rest of the photographers gathered in front of the dock and nodded.

He turned to his brother, stretched out his hand and smiled from ear to ear as he re-enacted his initial response. The scene felt somewhat contrived at the time, but I managed to take a photo and got the audio that I needed for the upcoming radio bulletin.

Addressing him again as “sir”, I thanked Mike for obliging to my request in such a friendly manner.

“My name is Mike. You can call me Mike,” he replied in a slightly pitched voice.

A few days after this brief interaction, I greeted Mike when I went to take pictures of the accused men in the dock, which I would then post to my employer’s Twitter feed.

I always found it uncomfortable standing in front of accused criminals in court to photograph them, and although Judge Eben Jordaan had granted permission for photographs to be taken and it was my responsibility to do so as a journalist, it never ceased to feel intrusive.

“Is that a phone you are taking pictures with?” Mike suddenly asked, looking at the slim white iPhone in my hand.

“Indeed,” I replied, confused by the question. I carefully observed Mike as he tilted his head and stared at the iPhone.

“But where are the phone’s buttons?” he asked.

Then it dawned on me. Mike had never seen a phone with a touchscreen before. “When was the last time you saw a cellphone, Mike?”

“I last used a cellphone in 2002. Mine still had buttons,” he quipped.

We both chuckled, and I turned the phone around to show him the touchscreen from a distance, fully aware of the watchful eyes of the authorities in court, and I swiped to show him how one simply tapped the glass screen to make a call.

“That is very interesting,” he said as he examined the slim piece of technology from the dock.

I took my seat in the public gallery, feeling as if someone had punched me in the gut. It had dawned on me that the nine years in which Mike had been locked up meant that he had entirely lost touch with the outside world and fast-moving technology.

Despite this uncomfortable realisation, I couldn’t believe my luck that I had just talked to one of the central Boeremag accused. In our brief exchange, I’d expressed my interest in getting a unique perspective of the trial from inside prison, something that had not been done before in this case. When I went back to the Jacaranda FM office after court, I couldn’t help wondering what Mike’s life was like in prison and what had led to his decision to become part of the Boeremag.

In court a few days later, a lawyer handed me a folded piece of paper over the bench.

“Mike asked that I give this to you.”

I looked up and saw Mike watching over his shoulder from the dock.

He nodded. Before I had a chance to open the letter, the court clerk bellowed, “All rise in court!” Judge Jordaan emerged from the door behind his bench wearing a bright red robe. He’d presided over the trial since 2003, and in that time his hair and neatly trimmed beard had changed to a crisp white.

Judge Jordaan took a seat in his burgundy leather chair and hunched over the notes before him. I felt as if the letter from Mike was burning a hole in my hand, and I couldn’t open it soon enough after adhering to the court etiquette of first giving Judge Jordaan my undivided attention until he took his seat. Finally, I nervously unfolded the handwritten letter:

Karin

You can visit me this weekend. You can decide whether you want to come on Saturday or Sunday, as long as you are inside the prison between 09:00 and 12:00.

You will have to fill out a form. My details are:

Name: M.T. du Toit

Number: *********

Indicate that the visit will be for one hour.

Very important: Don’t leave anything in your car, such as phones, cameras or other valuable items. Make sure to leave all these items at home, as they will otherwise only get stolen.

Regards, Mike