Robert Polito’s “After the Flood” traces how Bob Dylan’s late-career works reveal the richness of historical memory and creativity that continues to shape his identity as an artist.

Image: Liveright

David Kirby

On Page 76 of the 1959 Hibbing, Minnesota, high school yearbook, a certain member of the senior class is quoted as vowing “to join ‘Little Richard’” after graduation. That didn’t happen. Once this music prodigy changed his last name to that of a dead Welsh poet, young Bobby Zimmerman became - and is still becoming - one of the most inventive, prolific and enduring artists of our (or any) time.

The longer a career is, the more it’s scrutinised, with new work relentlessly compared with old. While it’s generally true that most musicians - think Jackson Browne, James Taylor, Don McLean (reader, I can already hear your objections) - put out their best work when they are young, there are exceptions, like Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Paul Simon.

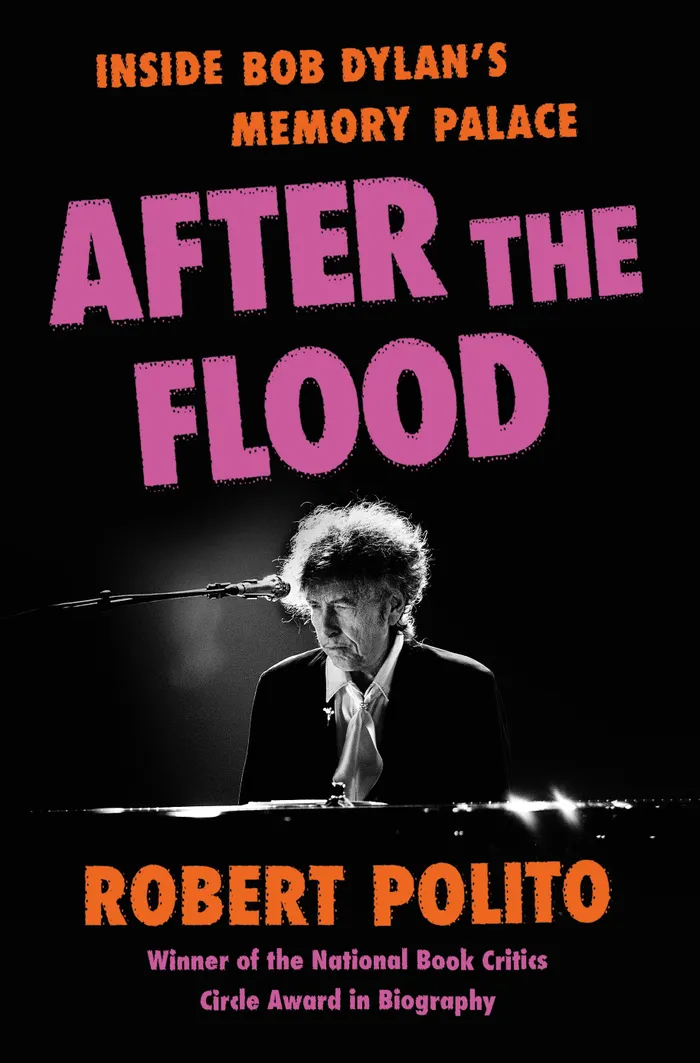

In his hyper-detailed and persuasive new book, After the Flood, Robert Polito examines the latter part of Bob Dylan’s career, from 1991 to 2024, the period between winning a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and his Rough and Rowdy Ways tour. Few would call this period a high point, but Polito feels otherwise. He points to the tremendous output - poems, novels, films and, of course, music - and refers to his biography as “a reconnaissance mission”.

Bob Dylan performs on stage at 'Les Vieilles Charrues' Festival in Carhaix, western France on July 22, 2012.

Image: David Vincent

Polito argues that during the past three decades, Dylan expanded his profile by building “memory palaces” in his songs, places that house books, people, historical facts, personal memories, snippets from forgotten songs, biblical quotations and whatever else pops into his agile brain. The result is songs that are as good as his early ones, if not as well-known, including Murder Most Foul and I Contain Multitudes, both of which Polito covers extensively.

A memory palace is a metaphor for a certain kind of mind, one that notices everything almost offhandedly yet can recall its exact position in time and place later, often seemingly without effort. It comes from the story of Simonides, who had stepped away from a banquet in ancient Thessaly just before the building collapsed; those present were crushed beyond recognition, but Simonides was able to identify each body because he remembered exactly where every guest was before the roof fell in.

Dylan has been following Simonides’s path in a way that sustains his work and, more important at this point, his status as a one-of-a-kind artist. In one example, Polito explains how the singer went to the New York Public Library to read newspaper reports on the Civil War that later showed up in his music. “I crammed my head full of as much of this stuff as I could stand and locked it away out of sight,” Dylan wrote in his 2004 autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, figuring “I could send a truck back for it later.”

The result is a body of work that continues to sell and be acclaimed by critics, even though it hasn’t overtaken popular culture the way his best-known songs have. Blowin’ in the Wind, Like a Rolling Stone and Tangled Up in Blue brought him early fame, so it’s little wonder that the recent biopic A Complete Unknown ends in 1965. His late-career resurgence is based on work that is denser, longer, more allusive, more steeped in history and earlier musical traditions. It’s not at all like those earlier voice-of-a-generation songs that are woven inextricably into our cultural fabric. Sure, there are fewer Top 40 hits, but during this time Dylan has only solidified his reputation as a seminal cultural figure; the Nobel Prize in literature he won in 2016 is further proof of that.

The Dylan that Polito describes comes across as a musical athlete who, even in his later years - he is now 84 - can do more with the beauties and burdens of this world than most anyone else. Polito is also a seasoned artist. His books over the years have dealt with poetry, painting, fiction and film and include an award-winning biography of the novelist Jim Thompson. Here, he focuses on creative process: As Polito sees it, Dylan’s later work increasingly resembles a collage, drawing threads from such disparate cultural and historical sources as crime novels, Civil War-era sermons, lyrics from forgotten 78 rpm records and other knickknacks that he then weaves into coherent songs.

In other words, Polito is neither a sweeping cultural historian nor a decoder. For an exploration of Dylan’s place in the larger scheme of things, there’s Greil Marcus’s Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (2005). For a close reading of his lyrics, your best bet is Christopher Ricks’s Dylan’s Visions of Sin (2003).

Polito approaches from a third angle: He uses an abecedarium, or “alphabet book,” approach to pluck out and riff on themes from Dylan’s late career. For example, in the “R” chapter, he begins with “rewrite” (which Dylan has always done), then goes on to “religion” (the singer has changed faiths publicly more than once and has described those shifts in his music) and, of course, the 2020 Rough and Rowdy Ways album and a key accompanying interview in Rolling Stone.

Is Polito’s approach challenging at times? Yes, but it’s worth it if you want a fuller sense of how the mind of one of our most challenging artists operates.

Related Topics: