Future of Scotch whisky lies in hands of US president who drinks diet coke

Drew McKenzie Smith is the founder and managing director of Lindores Abbey Distillery.

Image: Emily Macinnes/For The Washington Post

Emily Davies

Drew McKenzie-Smith was working as a chef in northwest England when a man knocked on his father’s door with news: A scroll from a long-dead king recorded the earliest known mention of Scottish whisky, and it was traced to the ruins of a monastery next door.

McKenzie-Smith, now 61, did his research, took a risk and built a distillery - entering a global industry subject to the shifting tides of war and diplomacy to honor his family and heritage.

He braced for recessions and regulatory headaches. He anticipated hard years. But he did not plan for the return of Donald Trump - or the possibility that the American president with Scottish roots could shape the fate of his distillery.

After Trump in April launched tariffs on the United Kingdom, McKenzie-Smith slowed his expansion into the US market, nearly grinding it to a halt.

“Whether you like it or not, this guy has the power to really damage Scotland,” he recalled telling his wife at the time. “But one thing that is unique about Trump is if you appeal to the individual, you might get somewhere.”

Scotland, the birthplace of Trump’s mother, Mary Trump, spent much of this week protesting against its prodigal son - a sober man whose drink of choice is Diet Coke. But while the land of whisky has long had a complex relationship with Trump, distillers are hoping a personal plea built on his affection for his mother’s homeland will help Scotch whisky escape the fallout from his global trade war.

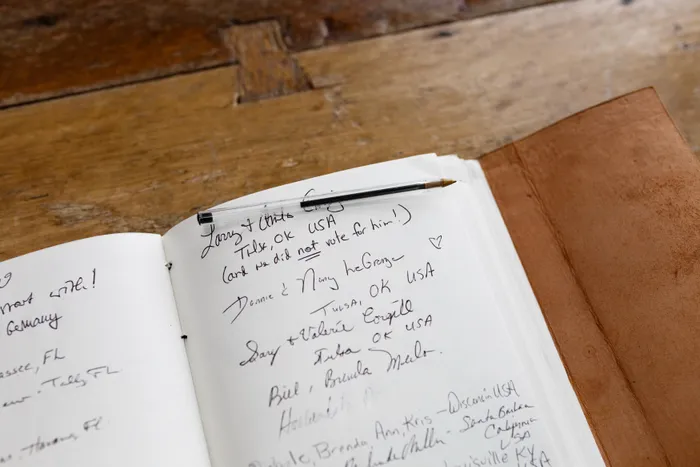

American tourists visiting Lindores Abbey Distillery made a point to say they did not vote for President Donald Trump.

Image: Emily Macinnes/For The Washington Post

Trump spend four days visiting his golf courses as tariffs against dozens of countries were set to take effect yesterday, giving Prime Minister Keir Starmer a quiet moment on the fairway to make a case for shielding the United Kingdom from further economic confrontation. Their meeting comes months after Trump first announced a de-escalation that spared certain UK exports, like automobiles, from higher tariffs but left room to hammer out the details - creating an opening for lobbying from affected sectors.

The Scottish - who as a whole are a more liberal, pro-European Union people and often feel overlooked by Westminster - saw this golf-oriented trip as their best chance at affecting negotiations between London and Washington. Despite recent Ipsos polling showing more than 70 percent of Scots do not approve of Trump, everyone from cabinet ministers to Lowland distillers say they plan a charm offensive in what amounts to a high-stakes weekend for the country.

Scotch whisky makers are facing 10 percent tariffs on exports to the United States, their biggest market.

“It is a vital employer, a major investor and an iconic export, and we want to see tariffs lifted on Scotch whisky as soon as possible,” Wendy Chamberlain, the Parliament member for North East Fife, where Lindores Abbey Distillery is, and chair of the all-party parliamentary group on Scotch whisky, said.

While groups in Scotland organized protests in Edinburgh,and Aberdeenshire, where Trump owns a golf course, the whisky trade associations in Scotland and the United States mounted an offensive, working together to try to persuade their respective governments to leave spirits out of their spat.

Lindores whisky bottles sit among supporters of the distillery.

Image: Emily Macinnes/For The Washington Post

“Scotch and American whisky, we are so intertwined,” said Chris Swonger, president and CEO of the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. “We are trying to make our colleagues in the Trump administration understand that.”

Bourbon, which is whiskey made in the US with a sweet, rich flavour, is aged in new charred oak barrels. Many of those barrels are shipped to Scotland and reused to age Scotch whisky, which is typically more varied in taste and always matured in secondhand casks for at least three years.

The distinct styles of the spirits and the sharing of barrels, as well as a consumer base that tends to like an array of options, make it so the cross-continental industries benefit from each other more than they compete. The US is Scottish whisky’s biggest export market - generating about 1 billion pounds a year, according to the U.K.’s Scotch Whisky Association - and is often the first international market that small distillers enter.

“We feel we are two different branches of the same family,” said Mark Kent, the U.K.’s chief executive of the Scotch Whisky Association. “Bourbon can only be made in the U.S. and Scotch can only be made in Scotland. There is no question of one side taking over another.”

Still, the spirits have a history of becoming collateral damage in trade wars. In 2019, during a subsidy fight between Airbus and Boeing, Trump’s first administration and the European Union imposed 25 percent retaliatory tariffs on a range of goods, including spirits: The US targeted single-malt Scotch, and the EU, which then included the UK, hit American bourbon and other whiskey.

“We’ve been through this pain before,” Swonger said, who is concerned that the United Kingdom could impose retaliatory tariffs if Trump continues to take aim at Scotch whisky. “This is creating a situation of immediate difficulty for our distillers at the moment.”

Back in the Scottish Lowlands, where rolling fields are sliced by narrow stretches of road, McKenzie-Smith stood before towering bronze distillers named after his daughters. They were built beside the field where, more than 500 years ago, Scots enjoyed what they now call “amber nectar.”

“With the incumbent in the White House,” said McKenzie-Smith, dressed in a vest that bore the name of his distillery, “the one thing we can count on is uncertainty.”

Lindores Abbey Distillery, in operation since 2017, had endured the hard years of the coronavirus pandemic. Now McKenzie-Smith was ready to expand, and like most small distillers around him, the United States had long been his first focus.

He developed a plan that would make the US his biggest market in two years and started talking to partners across the Atlantic Ocean who could help make it happen.

Then Trump was elected for a second time, an outcome McKenzie-Smith did not anticipate given the chaos he read about online during his first term. And soon enough, the American president’s stop-start economic strategy took hold - where one day there could be threats of sweeping global tariffs and the next day there could be talk of a deal.

“Even China won’t suddenly change the rules,” McKenzie-Smith said.

He said he started looking toward other markets, like India, where residents are known to have a thirst for Scotch. Earlier this month, Starmer and his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi struck a deal that slashed tariffs on Scotch whisky from 150 percent to 75 percent - still astronomically high but paving the way for a foray into what experts say is the world’s biggest whisky market.

Still, in the more immediate future, McKenzie-Smith said he needs the United States. So he started working with his partners abroad to craft language in negotiations that made any deal “subject to the tariffs being what they are on that day.”

He said the conversations have dragged on, slowly, as both sides wait to see what Trump decides and if that policy sticks.

“He’s changed the way we think about how we work with the States,” he said. “It’s not quite death by a thousand cuts, because we’re not dead yet.”