Chef wants you to try his gourmet bugs

This tostada is topped with chicatana ants. Christian Irabién, chef at Amparo Fondita, is cooking with bugs to show people a different side of Mexican cuisine and culture.

Image: Sarah Voisin/ The Washington Post

Nicolás Rivero

On the menu, the dish appears simply as “bichos,” meaning “bugs.”

Back in the kitchen, as onions, garlic and tomatillos sizzled in a mix of oil and mezcal, chef Christian Irabién sprinkled in a handful of nubby, black abdomens, about the size of peppercorns.

They were flying chicatana ants. A few weeks earlier, they had been snatched from the soil in Oaxaca, Mexico, as they crawled out of their nests fleeing summer rains. Now, they added a nutty crunch atop a toasted blue corn tortilla with fresh peaches and a creamy layer of avocado, lime and serrano pepper.

Irabién’s restaurant, Amparo Fondita, isn’t primarily about bugs. The sleek Dupont Circle establishment has been praised by the Michelin Guide for a wide-ranging menu that displays “creative and contemporary flair.”

But including some insects on the menu “is part of a mission to show people that Mexico isn’t just Señor Frog’s and Cancún and spring break,” said Irabién, who was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, and grew up in El Paso.

“If you’re out in the mezcal fields that are mostly worked by Zapotec communities, or if you’re in the Yucatan with Mayan communities, you’re sitting down and it’s like, ‘Hey, we’re having some bugs,’ and that’s just part of it,” he said.

Insects are an age-old source of protein in Oaxaca and a regular part of the diets of about 2 billion people around the world, according to a United Nations estimate.

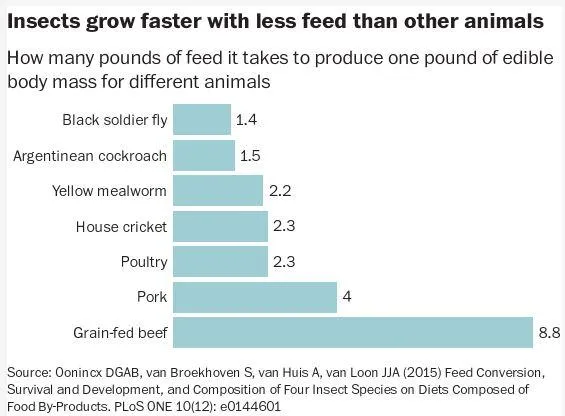

While for Irabién insect ingredients are a cultural touchstone, scientists say promoting bugs as food could also help the planet. Edible insects could feed a growing global population without requiring as much feed, water and land as livestock do, and without belching so much greenhouse gas.

A plate with tequila, mezcal and fruit is served with chicatana ants and grasshopper salt.

Image: Sarah Voisin/ The Washington Post

“A lot of insects that might not look that appealing are, in fact, very nutritious,” said J.P. Michaud, an entomologist at Kansas State University and a consultant for the Insect Farmers of America, a group that promotes bug farming. “If we could develop insects that are culinary delicacies, that would really enhance public perception and the appeal of insect consumption.”

Irabién invites D.C. diners to try a seasonal selection of insects. In August, his restaurant offered ants on tostadas, margaritas rimmed with grasshopper salt and whole red agave worms - a rare delicacy only available during the agave harvest, when Mexican farmers pull up the towering succulents and reveal the bugs burrowing among their roots. The worms are dried, cured and served alongside snifters of tequila and mezcal.

The taste is hard to describe.

Bugs can be nutty, citrusy, spicy or minerally, Irabién said, but that doesn’t really capture their full oddity.

“The bug spectrum of flavor is its own thing,” he said. “When people ask me what a grasshopper tastes like, I go, ‘They’re a little bit like worms.’ All right, well what do worms taste like? Kind of like grasshoppers.”

I tried the worms on a recent visit to Amparo Fondita, between the lunch and dinner rush. They were dry, crunchy, salty and a little oily, with a lingering metallic twang.

My video journalist colleague John Farrell described them as having a citrusy, acidic, mineral flavor with a little earthiness - “like eating dirt, I guess, if you recall what eating dirt was like as a child.”

I found myself absentmindedly snacking on them like bar nuts.

Red agave worms are a seasonal delicacy in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Image: Sarah Voisin/ The Washington Post

The ants were subtle in the ant tostada, which featured a bright, smoky concoction of sweet peaches, chipotle salsa and fermented garlic - with a hint of unfamiliar but not unwelcome nuttiness to remind you of the thorax between your molars.

Flavor aside, entomologists and food scientists see insects as miraculous machines for turning organic waste into high-quality protein and fat. Many farmed insects can eat by-products leftover from food processing plants, drink very little water and go from birth to maturity in a few weeks. They don’t need much land, and most edible species don’t burp planet-warming methane - or, if they do, their petite belches pale in comparison to cows’.

“Insects are extremely efficient,” said Arnold van Huis, an entomologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands who has published several books on eating insects, including “The Insect Cookbook.”

But the bugs aren’t easy to find, especially in the United States.

Irabién used to load up his suitcase with dried, compacted bricks of grasshoppers on his way back from visits to Mexico. Over time, he’s nurtured a network of people who can find him rarer breeds of top-shelf insects - including Ana Blanco, a lifelong Oaxaca resident who writes about mezcal and leads tours and tastings of the region’s distilleries and agave fields.

Blanco, 41, remembers catching grasshoppers in cornfields with cousins and friends on trips to the countryside when she was a child. Her grandfather collected worms that her grandmother would transform into salsas with “explosive flavor.” Back then, she said, “consumption was seasonal, limited and local.”

As Oaxacan cuisine has become more popular, she has started connecting chefs like Irabién with local families willing to sell a share of their insect harvest for as much as $100 a kilo. “Now you see a chicatana ant, and it’s like, ‘There go five pesos walking,’” Blanco said. “It’s like money coming up out of the ground.”

Christian Irabién, chef at Amparo Fondita, was born in Chihuahua, raised in El Paso, and was a sous chef at José Andrés's Oyamel. Currently, chicatana ants, red agave worms and grasshopper salt are on his menu.

Image: Sarah Voisin/ The Washington Post

Blanco said she only works with people who catch bugs sustainably, leaving behind enough wild insects to keep the population going. But as bug prices soar, she has seen the rise of small-scale grasshopper farms to supplement the wild catch.

An even larger, industrial insect industry is starting to take shape in the United States and Europe, with massive, mechanized farms teeming with billions of bugs. But, for now, these flies, worms and crickets go into pet food, livestock feed or pellets for farmed fish. Regulators have been slow to approve bugs in human food - and Americans and Europeans have been even slower to accept them.

“A big part of it is to let people come to this decision on their own without beating them over the head about how they must eat this,” said Joseph Yoon, a Brooklyn-based chef who tours the world giving talks and demonstrations to encourage people to cook and eat bugs. “My entry point is: It’s delicious - and also, it’s sustainable, nutrient dense and so forth.”

As he travels, Yoon tries to work insects into familiar dishes, serving up grasshopper poutine in Quebec or cricket mac and cheese in the Midwest. He doesn’t want to confront people with “a big bowl of bugs or a large insect on a skewer.”

“At the grocery store, we’re not just selling, like, a whole chicken with its head and feet still on,” Yoon said. “We’re selling different cuts of chicken, and we’re even selling chicken in jerky form or in different products.”

Including insect powder in protein bars or other processed foods could be an easy way to introduce bugs into people’s diets, scientists say. “It’s so far removed from the insect that people may accept it,” said van Huis, the insect cookbook author.

Insects are are great source of protein and an option as climate change hits hard

Image: Washington Post

But back at Amparo Fondita, Irabién said he’s taking baby steps to introduce diners to whole bugs, one meal at a time. Just getting a guest to look at bugs on a plate is a win, “even if it hits the table and you decide, ‘I thought I was going to want it but I don’t,’” he said.

“Now you’ve seen it. Now you know what it is. You got a little bit closer,” he said. “And maybe next time you come in, somebody else will order it and you’ll be two mescals in and you’ll be like, ‘Alright, fine, let’s do it!’” | The Washington Post