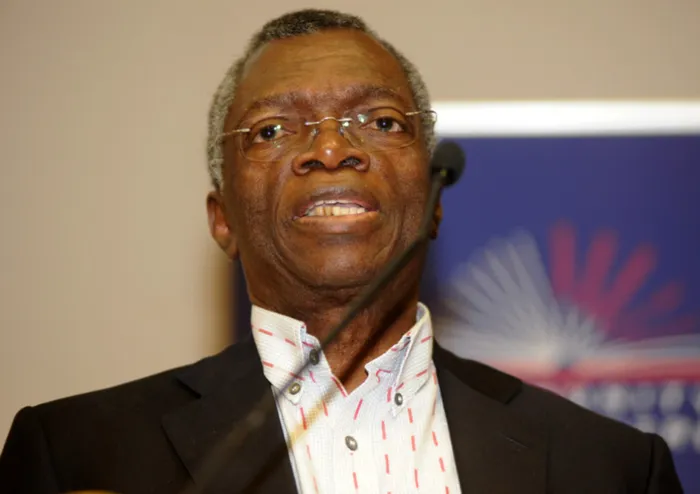

Farewell to a champion of the law

Cape Town 101006 Judge Pius Langa speaking during the Dullah Omar memorial lecture in UWC picture Ayanda Ndamane reporter Esther Lewis Cape Town 101006 Judge Pius Langa speaking during the Dullah Omar memorial lecture in UWC picture Ayanda Ndamane reporter Esther Lewis

Johannesburg - When former Chief Justice Pius Langa fell ill in April, there was concern. He had last been seen at a ceremonial Constitutional Court session in honour of Arthur Chaskalson, in February.

Law Society spokesman Krish Govender told journalists then, that Langa’s presence was very much needed in the country, and that South Africans still relied on him for his skills.

Indeed, even after his retirement from the Bench in 2009, he chaired the Press Freedom Commission which played a vital role in steering government and party control away from print media.

But unfortunately, illness took hold of the esteemed Langa, and he died on Wednesday morning at 74 at Milpark Hospital in Johannesburg where he had been a patient for about a month.

Born in March 1939 in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, Pius Nkonzo Langa had a childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. He described himself in an interview as being “distraught” when his parents told him they could not afford to continue paying for his education.

He was the second of seven children. But he refused to accept his fate and found himself a job first as a sorter in a clothing factory to fund his studies and then as an interpreter and messenger at the Department of Justice, where he hoped he might have an impact on the country’s iniquitous laws.

Langa carried on studying to become a prosecutor and then a magistrate, getting his B Juris from Unisa in 1973 and his LLB in 1976. He was admitted as an advocate a year later, in 1977, and then moved to kwaZulu-Natal to practise. Langa knew Durban well, having lived there as a child with his priest father.

A founder member of the Release Mandela Committee, Langa went on to assume a key role in many political trials, representing trade unions, civic bodies and anti-apartheid activists.

He obtained silk at the beginning of 1994 - a momentous year for the 55-year-old as he was appointed to serve on the Constitutional Court bench by Nelson Mandela. Although his brother Ben had been shot dead by ANC members who had false information on him in the 1980s, Langa bore no animosity. He served on the ANC’s constitutional committee, and advised the party at Codesa and at talks that led to the Groote Schuur and Pretoria minutes.

He believed that to be named one of the first 11 judges of the prestigious new court was an outright honour. And there was more to come: only three years later, Langa succeeded Ismail Mahomed as its deputy president, and in 2001, became the deputy chief justice.

In 2005, he was then-President Thabo Mbeki’s only candidate for Chief Justice upon the retirement of the first Chief Justice, Chaskalson.

Although he had been criticised for being “a transformation gradualist”, Langa strenuously denied this at his interview for the Constitutional Court’s top position. In fact, Langa told the Judicial Services Commission and then-Justice and Constitutional Development Minister Brigitte Mabandla that transformation of the judiciary was far too slow.

“My idea.. is more revolutionary,” he said, urging the wider inclusion of black legal practitioners.

Langa did not only champion black lawyers and advocates. He also accelerated the appointment of women to the Bench.

Langa insisted on a “zero tolerance” attitude towards discrimination in the judiciary. He also protected the independence of the judiciary which he said should “not feel beholden to anybody”.

“The strength of a democracy is measured by the confidence the public has in the judiciary and the court,” Langa told the panel at his interview.

The Law Society described him as heading “a transforming judiciary and legal profession with strength, humility and dignity”. Law Society chairpersons Kathleen Matolo-Dlepu and David Bekker wrote on Wednesday: “He remained a humble and vigilant proponent of the rights of the marginalised, oppressed and underprivileged.”

Although there are many judgments which reflect his measured insight, it was Langa’s eloquence in the 1995 ruling against capital punishment that is often cited.

“The test of our commitment to a culture of rights lies in our ability to respect the rights not only of the weakest, but also of the worst among us,” Langa wrote memorably in the ruling. “The Constitution constrains society to express its condemnation and its justifiable anger in a manner which preserves society’s own morality.

“Implicit in the provisions and tone of the Constitution are values of a more mature society, which relies on moral persuasion rather than force; on example rather than coercion. Those who are inclined to kill need to be told why it is wrong. The reason surely must be the principle that the value of human life is inestimable, and it is a value which the State must uphold by example.”

He earned himself an even wider political reputation in 1998 when he became the first black judge to be dispatched on a foreign mission as chair of the Langa Commission into the ill-fated Lesotho elections. The commission was appointed after opposition leaders claimed electoral fraud by the Lesotho Congress for Democracy, which had won the poll by a landslide.

But the report failed to satisfy many, and there was anger across Lesotho’s towns and villages. A revolt followed. Some analysts expressed disappointment that the final document had been delayed by the South African government, fearing it had been sanitised, yet this did not reflect on Langa’s integrity.

There was no such controversy around Langa’s handling of the Fiji Islands when, as a special envoy of the Commonwealth, he helped return the territory to democracy. Langa was also involved in democracy-building interventions in Sri Lanka, Zimbabwe, Rwanda and Tanzania, and was a member of the Judicial Integrity Group which compiled the Bangalore Principles for Judicial Ethics.

Langa was honoured by UCT, his alma mater Unisa, Rhodes, Yale and Northeastern University in Boston.

He served as Chancellor of the University of Natal and was a Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Southern Methodist University School of Law in Dallas, US.

He was widely praised for immersing himself in the good of civil society, joining the Democratic Lawyers Association during apartheid, and helping to start and run the National Association of Democratic Lawyers where he was known as Comrade Pius.

Langa’s wife Beauty Thembikile, to whom he was married for 43 years, died, also after a long illness, shortly before his retirement in 2009. The couple had five children and several grandchildren.

In an article he wrote in 1999, Langa summed up his views on being a judge: “The true measure of our functioning must lie in its rigour, sensitivity and creative character. It is on our success in these respects that I believe we should be judged.”

Langa surely passed with flying colours.

The Star