Japan is among the world’s biggest producers of cultivated pearls, which are having a renaissance in the fashion industry, for women and men alike.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

AGO BAY, Japan - For generations, a string of perfectly round, classic white pearls - the kind worn by fashion icons like Audrey Hepburn and Jacqueline Kennedy - has been the epitome of understated class. The lustrous “akoya,” coveted around the world for their timeless beauty, originated here, in the calm waters and sheltered inlets of Ago Bay, where conditions are ripe for oysters to thrive.

But after 130 years, Ago Bay’s pearl industry is facing a double-whammy existential crisis: Warming waters are endangering oysters, which are growing weak and susceptible to a deadly virus. Aging farmers are struggling to find successors for their small, family-owned businesses.

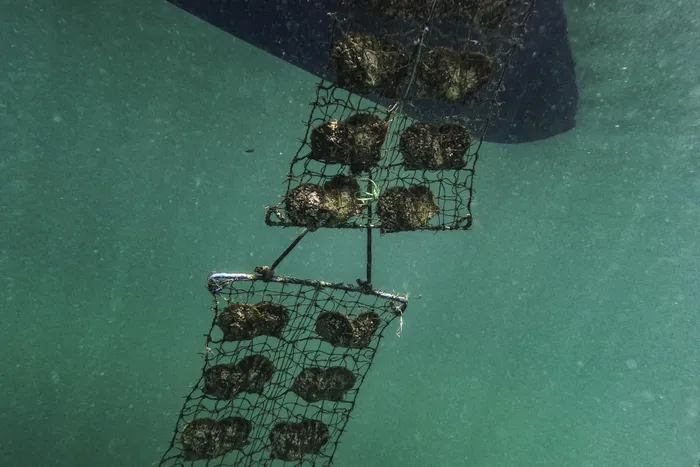

Takeuchi lowers his nets into the sea. It takes about two years for the spat to grow into “mother” oysters, ready for pearl cultivation.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

Akoya pearl oysters are carefully tended by farmers using techniques passed down through generations. After being artificially fertilised and incubated in tanks, the spat - or young oysters - are transferred to the sea. Farmers periodically inspect the bivalves and check on the water temperature to ensure a healthy growing environment. After another two years, they are harvested.

This process is becoming more precarious. Akihiro Takeuchi lost 80 percent of his juvenile oysters to a mysterious illness six years ago. Researchers identified it as a novel strain of the highly contagious birnavirus that had spread to farms throughout Ago Bay, wiping out most of a generation of new oysters.

They suspect the warming waters had made oysters - particularly the young ones, some as small as a pinkie nail - more susceptible to the virus. The waters around Japan have warmed by 2.4 degrees in the past century, with the average sea surface temperature in 2024 reaching the highest level since the Japan Meteorological Agency began keeping records in 1908, at 2.59 degrees higher than normal. The outbreak rattled the industry. In 2023, Japan produced 13.2 tons of pearls, the lowest since the government began keeping records in 1956 and a fraction of the peak of 138 tons recorded in 1967.

When ready for cultivation, “mother” pearls are transferred to nets on long ropes attached to buoys.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

But overseas demand is only growing. In 2023, Japan exported $290 million worth of pearls, the highest since 2000 - and this is being reflected in record-high prices. Sales have been especially strong from Chinese buyers shopping in Hong Kong, which represented 81 percent of exports last year, according to Japan’s fishery agency and exporters.

Oysters are happiest when the water is between 68 and 77 degrees. But summers in Japan are getting hotter and longer, and heat gets trapped in the protected waters of Ago Bay. The past two years, the water temperature has been as high as 86 degrees during peak cultivating season - a level that can be fatal to oysters.

To cope, pearl farmers and researchers are experimenting with selectively breeding shellfish to develop disease-resistant strains of akoya oysters that can withstand heat. They’re also moving oysters into deeper, cooler water. And they are taking steps to contain any viruses, like separating baby oysters and adult ones, which can be birnavirus carriers.

Pearl cultivation is a delicate process, the oyster equivalent of organ transplant surgery. First, the bivalves are stored together in a plastic bin, which calms them down. Think anesthetic for oysters. (Stressed oysters may make lower-quality or no pearls.) Then, a pearl farmer implants the “nucleus,” a tiny bead of shell and tissue from another oyster. Back in the water, the oyster secretes a shiny, iridescent substance over the bead that eventually forms a pearl.

The sheltered inlets of Ago Bay in Mie prefecture made it a natural home for the renowned “akoya” pearl industry.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

“The condition of the oyster before nucleation, the way the operation is performed, and the environment in which the oyster grows afterward - all of these factors have to come together perfectly for a high-quality pearl to form,” said Takeuchi’s mother, Michiyo.

Cultivated pearls have been popular since the process began in the 20th century, said Michael Coan, gemology professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. The akoya pearl, which is on the smaller side, became renowned because it was a “little powerhouse mollusk that had a great track record,” so shiny with an almost mirrorlike surface, Coan said.

“You knew what you were getting with an akoya cultured pearl necklace or jewelry,” Coan said. “You were getting the Rolls-Royce of pearls.”

A worker at the Union Pearl factory in Ise, Japan, sorts through cultivated pearls.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

But the environmental challenges are making it harder than ever to produce akoya pearls. So is the shrinking number of farms: In the past 30 years, the number of pearl farming businesses fell by 77 percent, government data shows. Part of the reason is because people like Takeuchi, a third-generation pearl farmer, have no successors.

With pearl farming becoming increasingly difficult, younger generations are choosing jobs in big cities, like Tokyo, rather than inheriting their family business. The uncertain future of Ago Bay’s main industry is a dire issue for the region, one of Japan’s top areas for pearl cultivation.

Related Topics: