Members of the civic organisation Black Sash protested against the apartheid government in the 1950s and envisioned a united democratic South Africa.

Image: Black Sash

From opposing apartheid laws to shaping social assistance policy in democratic South Africa, Black Sash, one of the country’s oldest civic organisations, has played a quiet but powerful role in the country’s democratic journey.

In 1955, when apartheid was at its height, a group of white women stood publicly against unjust laws while many remained silent. This led to the country’s first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, calling Black Sash, “the conscience of white South Africa”.

The initial founders were six white women: Jean Sinclair, Ruth Foley, Elizabeth McLaren, Tertia Pybus, Jean Bosazza, and Helen Newton-Thompson. The organisation was called the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League, and it was in response to the Senate Bill.

The Bill aimed to increase the number of government supporters in the Senate to pass the Separate Representation of Voters Act, which would remove Coloureds from the common voters' roll, violating an entrenched clause in the South African Constitution of 1910.

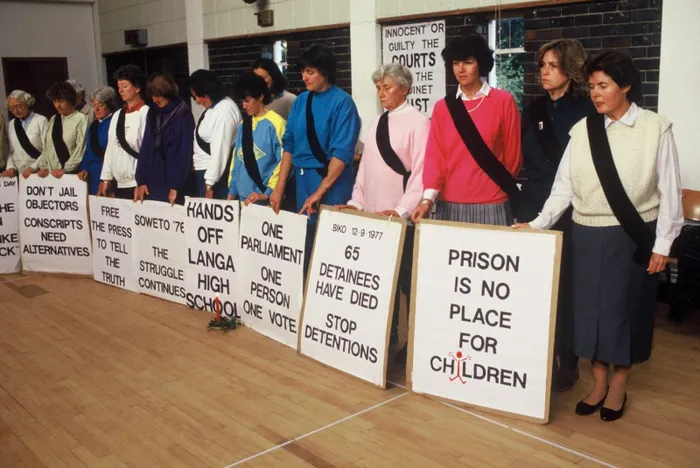

White women under the banner of Black Sash publicly protested against unjust laws by the apartheid government.

Image: Black Sash

The Women’s Defence of the Constitution League later became known as Black Sash, due to the black sashes worn by members during protests.

In 2025, the Black Sash celebrates 70 years of existence.

Rachel Bukasa, executive director of Black Sash, said the 70th anniversary marks a profound moment of reflection, recommitment, and renewal for the organisation.

“It is an opportunity to honour our legacy of principled resistance, civic courage, and people-centred advocacy while also confronting the urgent democratic challenges of our time. As we move forward, Black Sash’s role will continue to evolve as a watchdog, a mobiliser of grassroots power, and a champion of socio-economic justice, especially in defending the right to social protection for all in South Africa,” she said.

She added that the organisation’s legacy is a reminder that democracy without justice and accountability is hollow.

Members of the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League (now Black Sash) during the 1955 Constitutional Crisis, where the apartheid government introduced the Senate Bill, aimed to increase numbers of government supporters in the Senate to pass the Separate Representation of Voters Act which would remove Coloureds from the common voters roll, violating the South African Constitution of 1910.

Image: Black Sash

“Today, our work addresses the growing inequality, social exclusion, and erosion of trust in state institutions. Through monitoring grant delivery, challenging harmful policies, and mobilising for a universal basic income, we carry forward our tradition of confronting power with principled, grassroots-based advocacy. Our history gives us credibility and our present work ensures that this legacy stays active and relevant,” she stated.

Mandela’s words of calling the Black Sash “the conscience of white South Africa” recognised the moral clarity and civic bravery of the members, Bukasa said.

Black Sash members were among the few white South Africans who used their privilege not for protection, but for resistance. This idea of a “conscience” has transcended race and era today. We carry that same moral stance in challenging economic injustice, exclusion, and systemic failures that rob people of their dignity, she said.

Post apartheid, Black Sash’s mission is now pivoted towards realising socio-economic rights, especially for women, children, and marginalised communities.

Image: Black Sash

“Post-1994, Black Sash transformed from a white, middle-class, volunteer-led organisation into a professionalised human rights NGO grounded in constitutional democracy, inclusion, and grassroots organising. While we honour our early resistance against apartheid laws, our post-1994 mission pivoted towards realising socio-economic rights, especially for women, children, and marginalised communities.

“We shifted from silent vigils and advice offices to legal advocacy, community-based monitoring, policy reform, and digital rights education, all grounded in partnerships with community-based organisations and activists,” Bukasa said.

She stated that, like many civil society organisations, they face challenges around sustainable funding, especially for long-term advocacy and grassroots mobilisation. Public attention is often fleeting, and defending the poor and marginalised can be politically unpopular.

Rachel Bukasa, executive director of Black Sash, said that the organisation’s legacy is a reminder that democracy without justice and accountability is hollow.

Image: Black Sash

“But our strategic goals remain clear: achieving universal social protection, including a Basic Income Support grant; strengthening our national community monitoring network; influencing policy and practice through evidence-based advocacy; and deepening our commitment to building the next generation of social justice leaders.

“We’ve embraced digital advocacy while still prioritising offline organising for communities without digital access. Our Helpline, WhatsApp-based support, and online campaigns give beneficiaries immediate tools to challenge grant exclusions. At the same time, our Community-Based Monitoring work ensures we are grounded in the daily realities of people navigating public services. We also use digital platforms for civic education, amplifying voices from the ground in national policy conversations,” Bukasa explained.

She added that some of the organisation’s former members recall the silent vigils outside Parliament, holding up placards while facing police intimidation, public harassment, and social ostracisation.

Others speak about working in Advice Offices, helping Black South Africans navigate the pass laws and unjust detentions, often in secrecy. The personal risks were real, but so was the deep conviction that justice could not wait.

During a recent 70th anniversary celebration at the Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, Judith Hawarden, an early activist, narrated how a group of women got together in a series of pickets, protests, and other campaigns that placed human rights issues at the centre of the injustices of the apartheid regime.

“When the apartheid regime tried to flex its muscles and tried to change the laws in Parliament, six women became outraged as they could not allow this injustice and racist law to go unchallenged, and each one of these women went home and called on other women to join in,” Hawarden said.

She added that she had the rare and sometimes intense privilege of growing up in a household where a spy wasn’t a board game and line tapping wasn’t a hand strike.

Their home telephone would ring late at night, sometimes for courage, sometimes for intimidation, and her mother would be hunched over at her desk, always writing, always phoning, always doing.

“It’s hard to believe that what began as a group of deeply determined housewives in hats is now a national network with impact, intellect, and integrity.

“The Black Sash I salute today has evolved into a sharp, professional NGO, still fiercely rooted in its human rights mission, and with none of the condescension that often comes with institutional maturity,” Hawarden said.

Bishop Malusi Mpumlwana from the South African Council of Churches stated that the Black Sash’s emphasis was on unjust laws such as pass laws, forced removals, and Bantustans.

Mpumlwana added that the lost fundamental was about the search for information through its information services that continue to equip ordinary people with information to navigate the minefields of the apartheid regime and its unjust laws.

He urged the organisation to see how they can educate the youth more.

gcwalisile.khanyile@inl.co.za

Related Topics: