Black Wednesday: The Impact of SANEF's Exceptionalism on Journalism and Democracy

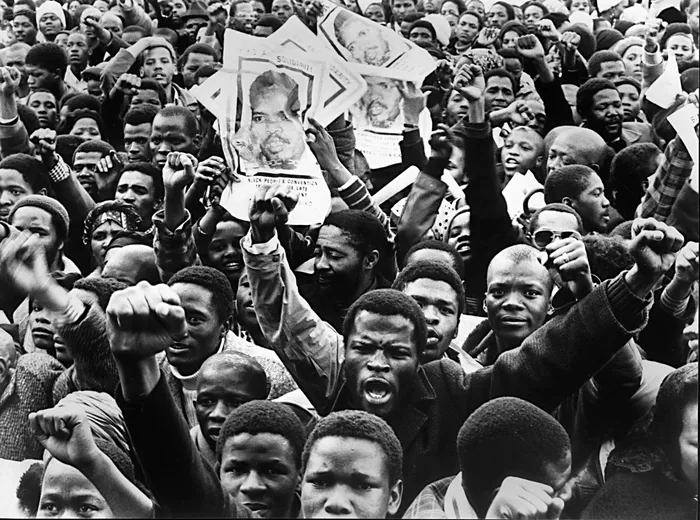

MOURNERS at the funeral of Black Consciousness (BC) leader Steve Biko in King William’s Town on September 25, 1977. In the aftermath of Biko's murder the apartheid regime banned 19 BC organisations, newspaper The World, The Weekend World and Editor Percy Qoboza was detained without trial.

Image: Independent Media Archives

Clyde N.S. Ramalaine

Indonesia’s Abie Zaidannas reminds us that “media plays important roles in a democratic society and cannot be separated from the democracy itself. Ideally, the media is a tool to educate voters, giving them facts, news, and balanced opinions about how the government is run and managed. Well-informed voters ensure accountable governance. Media also acts as a watchdog, facilitating people to articulate their views, demands, and aspirations, keeping politicians and public officials in check.”

Zaidannas’ perspective captures the aspirational vision of the media as democracy’s conscience, educating citizens, restraining power, and preserving public trust. Yet, in South Africa, this ideal remains increasingly distant. The press often functions within webs of political, commercial, or personal interests, eroding its impartiality and diminishing its capacity to act as a genuine pillar of accountability. Theoretically, the Fourth Estate stands for integrity and independence; in practice, the lived reality often betrays this noble promise.

To understand the depth of this departure, one must revisit the moral standard that once defined South African journalism.

On October 19, 1977, remembered as Black Wednesday, the apartheid regime banned The World and Weekend World newspapers, alongside nineteen Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) organisations. The crackdown came barely a month after the death of Steve Biko in police detention. It was a deliberate strike against dissent, an effort to extinguish the radical conscience of a nation awakening to its oppression.

Journalists such as Percy Qoboza, Joe Thloloe, Mathatha Tsedu, and Don Mattera were detained without charge, punished for giving voice to Black thought and pain. That day marked not just the silencing of papers, but the betrayal of truth by a government that feared words more than weapons. Black Wednesday thus became a moral benchmark for journalistic integrity: the refusal to serve power, even at great personal cost.

Yet, nearly five decades later, the struggle is no longer against overt censorship but against a more insidious form of capture, from within the media itself.

The “Fourth Estate” is revered as the watchdog of democracy, an institution meant to expose power, not protect it. Yet, in post-apartheid South Africa, this concept has been selectively invoked. Media houses frequently claim the mantle of press freedom to deflect legitimate criticism, equating oversight with oppression.

Independence is undermined when journalists align with political elites, defend certain figures uncritically, or target others with coordinated campaigns. In such instances, the Fourth Estate becomes less an instrument of accountability and more a rhetorical shield, a symbol used to claim moral authority while evading scrutiny. This selective invocation of freedom leads directly to the troubling phenomenon of compromised journalism that now defines our media reality.

Today’s media landscape reflects a troubling reality: many journalists have ceased to be impartial observers and have become political actors in their own right. They engage in factional battles, amplify selective narratives, and wield credibility as a political tool. The lines between reporting, advocacy, and manipulation are blurred beyond recognition.

Through privileged access to political elites, coordinated messaging, and selective framing, journalism risks transforming from a public trust into an instrument of influence. This corrosion of credibility undermines public faith in the press and hollows out democracy’s capacity for self-correction. When journalists become stakeholders in political and economic contests, the media ceases to hold power accountable; it becomes part of the power it was meant to challenge. Nowhere is this distortion more visible than in the conduct of SANEF, which claims to defend the press but too often shields it from accountability.

The South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) positions itself as the guardian of media freedom, representing editors, senior journalists, and media executives. Its mandate, to promote ethics, defend press freedom, uphold independence, and ensure accountability, is foundational to any democracy. Yet, SANEF’s conduct often betrays these principles.

In practice, SANEF embodies a form of exceptionalism rooted not in courage but in convenience. It proclaims independence while acting as a political broker, crying wolf at every instance of critique while remaining silent on internal bias and ethical breaches. Editorial gatekeeping, selective outrage, and partisan loyalty now define its posture. The moral clarity of 1977 has given way to a journalism of networks rather than conviction, comfort rather than conscience. The recent Mkhwanazi testimony exposes precisely how SANEF’s posturing collapses under the weight of its hypocrisy.

The recent testimony of Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi before Parliament exposes this crisis of self-perception. On October 8, 2025, SANEF condemned Mkhwanazi’s remarks, calling for penalties against journalists who engage in unlawful acts, portraying them as a grave assault on media freedom. In doing so, SANEF sought to draw equivalence with apartheid-era repression, invoking the spectre of Black Wednesday.

It is egregiously disingenuous for SANEF to invoke Black Wednesday in this context, as if journalistic scrutiny were state persecution. To equate legitimate questioning of compromised media actors with apartheid censorship trivialises the genuine sacrifices of 1977. SANEF’s selective outrage reveals not solidarity with truth but self-preservation disguised as principle. This episode underscores a deeper pathology, SANEF’s entrenched belief in its own moral exceptionalism.

Freedom of expression is sacred in democracy, but so is equality before the law. SANEF’s response to Mkhwanazi reflects a mindset of entitlement, assuming journalists merit exceptional protection regardless of conduct. Four axes define this distortion:

- Media Power – Major outlets wield immense influence, yet SANEF presents journalists only as victims, evading institutional accountability.

- Journalists as Political Actors – History shows the media’s complicity in factional politics, but SANEF’s rhetoric ignores this.

- Corruption and Inducements – Ethical breaches and financial compromises are real, yet SANEF’s blanket defences risk shielding misconduct.

- Equality Before the Law – By resisting lawful oversight, SANEF promotes dual standards, eroding democratic legitimacy.

This is not the defence of freedom; it is the distortion of it. Still, the solution lies not in dismissing SANEF altogether but in calling it back to its founding conscience.

To be fair, SANEF’s interventions remain justified when confronting genuine threats such as illegal surveillance or state intimidation. However, its credibility depends on distinguishing between oversight and oppression. Defending press freedom must never become a pretext for evading accountability. Thus, SANEF’s redemption depends not on louder outrage, but on moral recalibration.

SANEF occupies a pivotal role in South Africa’s democracy, yet to regain moral authority, it must embrace accountability with the same zeal it demands of others. Recalibration requires:

- Internal Accountability – Enforce ethical standards and address conflicts of interest.

- Acceptance of Oversight – Recognise that lawful critique strengthens, not weakens, democracy.

- Legal Precision – Advocate for genuine protections without shielding malpractice.

- Public Engagement – Rebuild trust through transparency and integrity.

The press of 1977 was punished for challenging state power; today’s media risks irrelevance for failing to challenge itself. Integrity cannot coexist with factional loyalty, nor can credibility be traded as political currency.

To invoke Black Wednesday today is not nostalgia; it is moral accounting. It demands that the journalism which once confronted tyranny rediscover its conscience, or risk being remembered not for its freedom, but for its fall.

* Clyde N.S. Ramalaine is a theologian, political analyst, lifelong social and economic justice activist, published author, poet, and freelance writer.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.