How South Africa can secure safer water through faster testing and community engagement

EARLY DETECTION

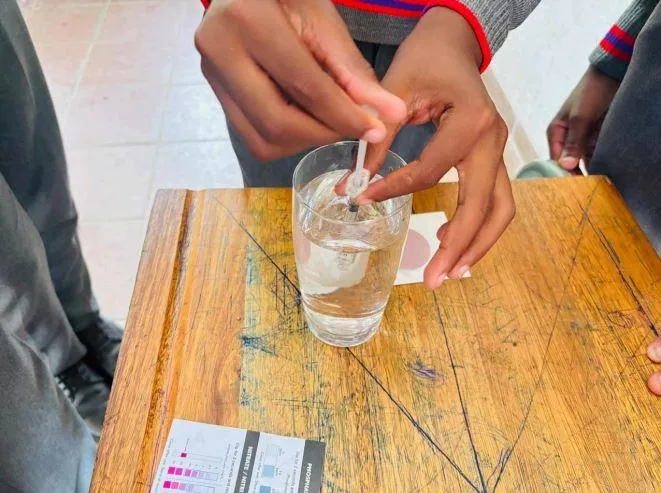

Pupils participate in a school water quality testing project led by environmental organisation WaterCAN, which found that 43% of school water samples tested were unsafe for drinking. The writer calls for n-house testing for early warnings and collaboration between municipalities, companies, and communities to address South Africa's water-quality issues.

Image: Supplied

Access to safe and clean water remains a critical concern in South Africa. Recent incidents, including a highly contaminated water sample from Secunda that showed extreme levels of E. coli, have highlighted the urgent need for faster and more reliable water quality monitoring across the country. Public health depends on the safety of the water flowing through our rivers, dams and municipal systems, yet current monitoring processes often struggle to detect contamination before it reaches communities. Improving these systems will require a combination of practical testing methods, independent oversight and community involvement.

Why traditional testing cannot keep up

South Africa’s public water testing framework is accurate, but slow. When contamination is suspected, samples must be collected, couriered to an accredited laboratory and cultured to detect biological threats such as E. coli. While potential of Hydrogen (pH) and chlorine levels can be measured quickly on site, biological tests take one to two weeks because the organisms must be grown before results can be confirmed. This delay leaves a dangerous gap in which water quality could deteriorate without immediate detection.

The process is also costly. A single accredited test, including logistics, can cost around R5 000, which makes frequent testing inaccessible for households and many community organisations. As a result, many people rely on the assumption that water from the tap is safe. When contamination does occur, individuals may fall ill without realising the cause, because there is no real-time feedback on water quality.

How in-house testing can speed up detection

Although accredited labs are still required for official reporting, new approaches are emerging that can help organisations identify risks earlier. Some companies are now investing in equipment that allows them to carry out basic testing in-house. These tests are not accredited, but they give fast, useful readings that act as early warning indicators. If an organisation detects abnormal results, it can immediately escalate the matter to an accredited lab instead of waiting for contamination to spread.

Routine pH and chlorine monitoring also plays a valuable role. These tests are inexpensive, easy to perform and can be carried out continuously within businesses or local facilities. While they cannot detect biological contamination, they help ensure that the chemical balance of the water stays within safe limits. When combined with monthly or cyclical biological testing, this creates a more proactive monitoring system.

This approach recently proved critical in Secunda, where a business conducting its own branch-level testing discovered that municipal water entering the site was contaminated with sewage. The in-house test flagged the issue quickly, prompting further investigation. Without this internal programme, the problem might have gone unnoticed for far longer.

Why collaboration improves water safety

A stronger water monitoring system cannot rely on public authorities alone. Partnerships between municipalities, private companies and communities can help improve both the speed and reliability of responses. Independent testing at business level introduces greater transparency and can highlight water quality issues that may otherwise go unreported. When patterns of poor quality emerge, communities gain evidence to push for corrective action.

Transparency also drives accountability. If businesses in a region consistently report poor water quality, it becomes more difficult for the problem to remain hidden. Public pressure increases and municipalities have a clearer picture of where urgent interventions are needed. This type of shared visibility is essential for strengthening trust and promoting faster action.

Communities have an important role as well. Residents are often the first to notice discolouration, odour or unusual cloudiness in their tap water. Reporting these signs to employers or organisations with the means to test can lead to early detection. Raising issues solely through political channels may not always lead to immediate investigation, but involving local businesses can create quicker pathways to testing and response.

Robert Erasmus is Managing Director at Sanitech.

Image: Supplied

A path toward safer and more reliable water

A safer water future for South Africa will depend on strengthening both formal and informal monitoring systems. Accredited labs remain vital for official results, yet in house testing, routine checks and community reporting can highlight risks long before formal samples are processed. When contamination is confirmed, solutions like filtration, Ultraviolet (UV) treatment or proper chlorination can be deployed quickly to restore safety.

What this shows is simple: the safety of tap water cannot be taken at face value. Consistent monitoring and transparent reporting are key to safeguarding public health. With better co-ordination between public bodies, private organisations and communities, South Africa can build a water monitoring system that identifies problems early and protects every household.

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or the Independent on Saturday.

Robert Erasmus is Managing Director at Sanitech.

IOS

Related Topics: