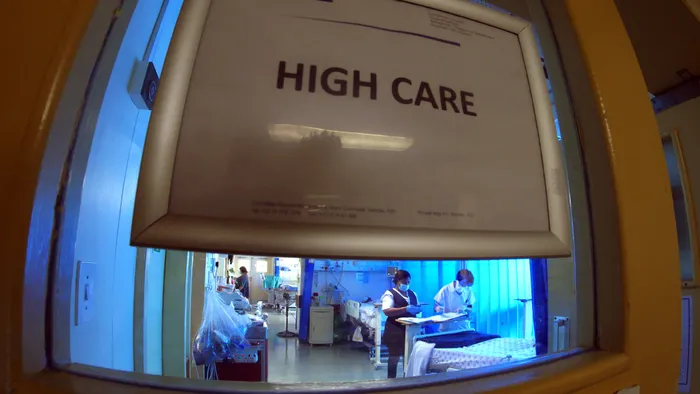

South Africa’s deadly shortage of ICU beds and staff

Health crisis

South Africa is facing a critical shortage of ICU beds and skilled staff to man those units .

Image: Ian Landsberg / Independent Newspapers Archives

DON'T hold your breath if you need an ICU bed. South Africa has just five ICU beds per 100 000 people - far below the global average - leaving critically ill patients at risk of preventable deaths.

Research by Professor Fathima Paruk, head of Critical Care at the University of Pretoria, who the Department of Health has confirmed has been granted permission to conduct a national ICU audit, warns that ICU capacity lags far behind international standards, Germany has 39 beds per 100 000 people; South Africa has just five, with some provinces closer to one.

“Hospitals will need more ICU beds as patients live longer,” Paruk said. “Intensive care saves lives, but it requires trained staff, technology, and resources that many hospitals simply don’t have. The demand is growing faster than the system’s ability to respond.”

Many critically ill patients are stabilised in smaller hospitals before transfer, sometimes too late, leading to preventable deaths.

The Department of Health said it could not confirm the exact number of ICU beds nationally, noting that no recent audit has been conducted and that future interventions will be guided by Prof Paruk's audit findings.

Foster Mohale, from the Department of Health, said while both public and private ICU capacity is considered in planning, “beds alone are not enough - intensive care requires highly trained specialists, and patients are often stabilised in smaller hospitals before transfer to facilities with ICU capacity.”

“You can’t run an ICU bed without nurses and doctors who are trained in critical care, and we are extremely short of them in both the public and private sectors,” Paruk added. “Across the country, only 25% of our ICU nurses are trained in critical care.”

Health workers on the frontlines, the ICU shortage is only one symptom of a deeper crisis: hospitals face collapsing infrastructure, water and power shortages, and severe understaffing.

Dr Dumisani Bomela, CEO of the Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA), told the 'Saturday Star' this week that the country’s healthcare system is buckling under systemic and avoidable problems, many documented in Presidential Health Summits, the Health Market Inquiry, and other reports.

“The challenges include a longstanding human resource deficit, decaying infrastructure, fragmented service delivery, and incomplete reforms,” said Bomela. “Critically, there is insufficient collaboration between the public and private sectors, something HASA has long advocated for. Collaboration is not optional; it is essential.

“But technology alone cannot solve the crisis,” he added. “Investment in professional development and training is vital. The private sector has both the capacity and the will to support employment and skills development, helping to address healthcare and national employment challenges.”

While these issues are widespread, provinces like Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal feel them most acutely.

This week, the National Education, Health and Allied Workers’ Union (NEHAWU) issued a stark warning about healthcare facilities in Gauteng. Mzikayise Tshontshi, NEHAWU’s provincial secretary, said they had compiled a memorandum outlining the scale of the crisis.

“Infrastructure and utilities are crumbling ... staffing shortages leave workers stretched ... (and) patients are left unattended for hours,” Tshontshi said.

Ironically, in some facilities, patients are more likely to be protected than treated.

“Financial mismanagement has seen security budgets outweigh clinical budgets, leaving hospitals under-equipped and communities underserviced. Employee relations departments lack the capacity to address grievances, leaving staff morale at an all-time low,” Tshontshi added.

He warned that these conditions expose both workers and patients to unnecessary danger, erode community confidence in the public health system, and ultimately undermine South Africa’s constitutional right to healthcare.

“These are not isolated problems but systemic failures that have persisted for years,” he said. “Our members continue to serve with dedication despite working under intolerable conditions.”

NEHAWU’s memorandum calls for immediate government intervention to address what it describes as a deepening healthcare crisis.

In KwaZulu-Natal, experts say the problem goes beyond ICU bed availability to everything that supports intensive care.

Dr Imran Keeka, DA MPL and Member of the Health Portfolio Committee, said the burden of disease and trauma has created shortages not just in ICU beds but also in specialised nurses and specialists. The ICU situation was closely examined especially at Northdale and Greys Hospitals in Pietermaritzburg.

“While these facilities certainly need more beds, increasing beds means increasing staff and expertise. All of this requires funds. In the current fiscal climate, this is not possible. Our engagement with Greys Hospital revealed the need for an additional 10 beds. They contend they are capacitated to handle the additional beds from a staffing point but barely, if at all, allocated. These shortages have forced regional hospitals to provide backlog services they are not equipped for. In other words, shortages exist at all levels of ICU care across disciplines, from paediatrics to cardiology.”

Feminist and social justice activist Yolanda Dyantyi said the decay in the health system cannot be separated from a broader crisis of accountability and corruption in public institutions.

“Whistleblowers’ lives have been shown to be worthless in South Africa,” Dyantyi said. “People who try to do the right thing are being assassinated for upholding their oaths as public servants.”

She warned that systemic corruption in the public health sector represents “a criminal justice failure of national proportions. To steal at such a scale requires complicity across multiple levels of administration. This also highlights the scary fact that as citizens, we are literally held hostage by criminals.”

The most prominent victim was Babita Deokaran, a whistleblower who uncovered large-scale corruption in the Gauteng Department of Health where she worked as an accountant. For her efforts, she paid with her life.