The wild Irishman who masterminded a jailbreak during a British and Irish Lions tour of South Africa

RUB OF THE GREEN COLUMN

Paddy Mayne Springbok captain Danie Craven is to the left of British and Irish Lions lock Paddy Mayne (with ball, right) during the 1938 series in South Africa. Photo: SUPPLIED

Image: SUPPLIED

Rub of the Green Column

The British and Irish Lions squad that is about to tour Australia will arguably be the most professionally prepared rugby unit the world has seen.

Coach Andy Farrell has been given every resource to ensure the finest players of the UK and Ireland smash the Wallabies.

But one wonders if the drive to excel can erode the spirit of touring that has been the wonderful charm of so many Lions tours.

My mind goes back to the tales of the Lions’ tours to South Africa, where terrific battles on the rugby pitch were rivalled by the exploits off it.

I think of Paddy Mayne, the wild Irish rover who lit up the 1938 tour to South Africa, the year before World War II broke out.

Mayne would win more awards for bravery in that horrific conflict than any other soldier, and his larger-than-life persona was colourfully apparent the year before in South Africa.

Mayne was a well-educated man, a solicitor in Belfast, but he was also insanely restless and freakishly strong.

Early in the tour, Mayne found himself bored in a backwater town before the game against Eastern Transvaal.

He knocked on a teammate’s door and asked the fellow to come out with him.

When his invitation was declined, he methodically smashed into toothpicks every item of furniture in the room, leaving his teammate stranded in a sea of sticks.

But let’s backtrack to discover more about the monumental Mayne.

Not long before the Lions departed for South Africa, Mayne had played lock for Ireland against Wales in Belfast.

After one of his teammates had been kicked by a Welshman, Mayne retaliated with a fierce punch to the nose of the culprit.

Mayne’s mother and sister Frances were in the crowd, and while Mayne feared no living creature, he deeply revered his mother and sisters.

At halftime, Frances was sent to give a message to her brother. It read: “You must wipe the blood off the Welshman’s face at once.”

Mayne went to the Welsh huddle and dutifully wiped the face of the terrified Welshman, to the consternation of the Ravenhill crowd.

“Now,” he said, “look up at the stand and smile at my mother, or I will break every bone in your body in the change-room after the game.”

Earlier that year, also against Wales but in Cardiff this time, the great Welsh flyhalf Cliff Jones jinked through the Irish defence and crossed the tryline at the corner flag.

Instead of grounding the ball, he jogged triumphantly toward the posts, failing to notice Mayne looming up behind him.

Mayne scooped him up and carried him, as if a child, over the dead-ball line and dumped into the shocked crowd.

It was such a feat of strength that the rest of the Welsh team did nothing.

In 1938, South Africa’s stadiums were different from the modern-day arenas.

A stadium typically consisted of a concrete grandstand, plus temporary steel scaffolding that soared precariously skyward.

When the Lions arrived at Ellis Park midweek to inspect the pitch ahead of the Test match, the scaffolding was being erected by prison labour.

The prisoners were being housed in a compound at the stadium.

Mayne asked a prisoner what crime he had committed.

The fellow said he had stolen chickens and was serving a seven-year sentence.

Mayne, perhaps stung by recollections of Irishmen being deported to Australia by the English in the great Irish potato famine of the 1850s, for menial crimes such as stealing bread, decided to free the prisoner, whom he had christened Rooster.

That night, Mayne and a teammate called Bunners Travers, a tough Welsh coal miner, snuck back to Ellis Park with bolt cutters and clothes for Rooster, and freed him from the compound.

Rooster was on the run for a few days, but was stopped when a policeman thought he looked suspiciously well dressed.

The copper found hotel note paper in a pocket and the clothes were traced to the British team... and to Mayne.

The only reason Mayne was not sent home was because he was the team’s best player and crucial to dealing with a powerful Springbok team that had just returned from winning a series in New Zealand.

Mr Rugby, Danie Craven, who played in the 1937 series defeat of the All Blacks and was captain in all three Tests in 1938, said this of Mayne: “He is the toughest forward I have ever seen – never shy to exact retribution!”

Meanwhile, Mayne continued his roving unperturbed. When the tour reached Durban, a bored Mayne contrived to have some fun.

Again with his sidekick Travers, they dressed up as sailors and prowled the roughest pubs at the harbour, causing so many fights that The Natal Mercury carried a report about unrest in the harbour.

Both made it back to their hotel intact and unnamed.

It was Cape Town that witnessed Mayne’s tour de force.

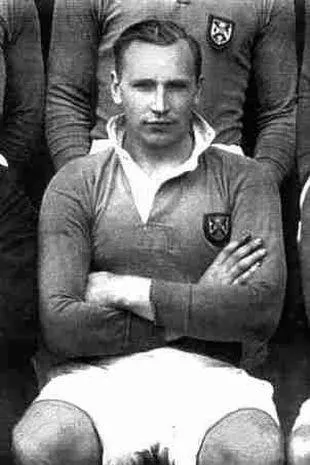

Paddy Mayne Paddy Mayne. Photo: SUPPLIED

Image: SUPPLIED

The Lions players were walking from their hotel to an official function, resplendent in white dinner suits, when Mayne spotted a group of men sitting outside a bar with rifles and lamps.

Mayne, a skilled marksman, was curious and quietly peeled off from his group and joined them.

It turned out these men were on their way to the outskirts of Cape Town for a nocturnal hunt.

Mayne’s roommate, George Cromey, read until 3am in his bed, waiting for Mayne to return.

He had just given up and was dozing off when the door was flung off its hinges and a triumphant Mayne stood in the doorway and proclaimed: “I have just shot a springbok!”

A highly alarmed Cromey switched on the light, and there was Mayne, his white suit streaked in red, with a four-legged springbok draped over his shoulders.

“The boys have been complaining that the meat in South Africa is not as fresh as at home,” Mayne beamed.

He then proceeded to captain Sam Walker’s room and flung the animal at him, adding: “Fresh meat for you, Sammy!”

Unfortunately, one of the horns jabbed into Walker’s thigh and he could not play for two weeks.

But how to dispose of the antelope?

Mayne knew that the manager of the Springboks was staying in the same hotel.

This fellow had a balcony outside his room, and Mayne climbed up to it with the bok and hung it over the railing with a note attached: “A gift of fresh meat from the British Lions rugby team.”

* Independent Media rugby writer Mike Greenaway is the author of The Fireside Springbok, a collection of South African rugby tales.

Related Topics: