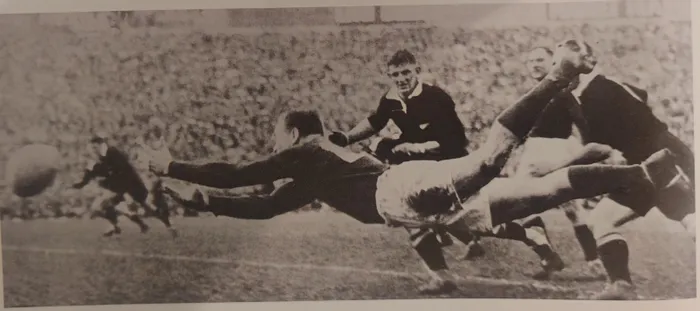

Danie Craven's famous dive pass caught the imagination of New Zealand. | Archives

Image: Archives

When Rassie Erasmus takes his Springboks to Auckland next week they will be hoping to tread in the majestic boots of the 1937 Springboks, the only Bok team to beat the All Blacks at Eden Park.

The awe-struck Kiwis rated the 1937 Boks higher than any of their All Blacks teams and bestowed on them the title “The greatest team to leave New Zealand’s shores.”

The Boks’ Eden Park victory took place 50 years before the first official World Cup final, which was played at the same venue in 1987 when the All Blacks defeated France. The match at Eden Park in 1937 was seen as the final of an unofficial word championship between the two best teams in the world.

To understand the frenzy that the ’37 Springbok tour engendered, some 5000 fans gathered outside the Metropole Hotel in Cape Town simply to hear the squad being announced.

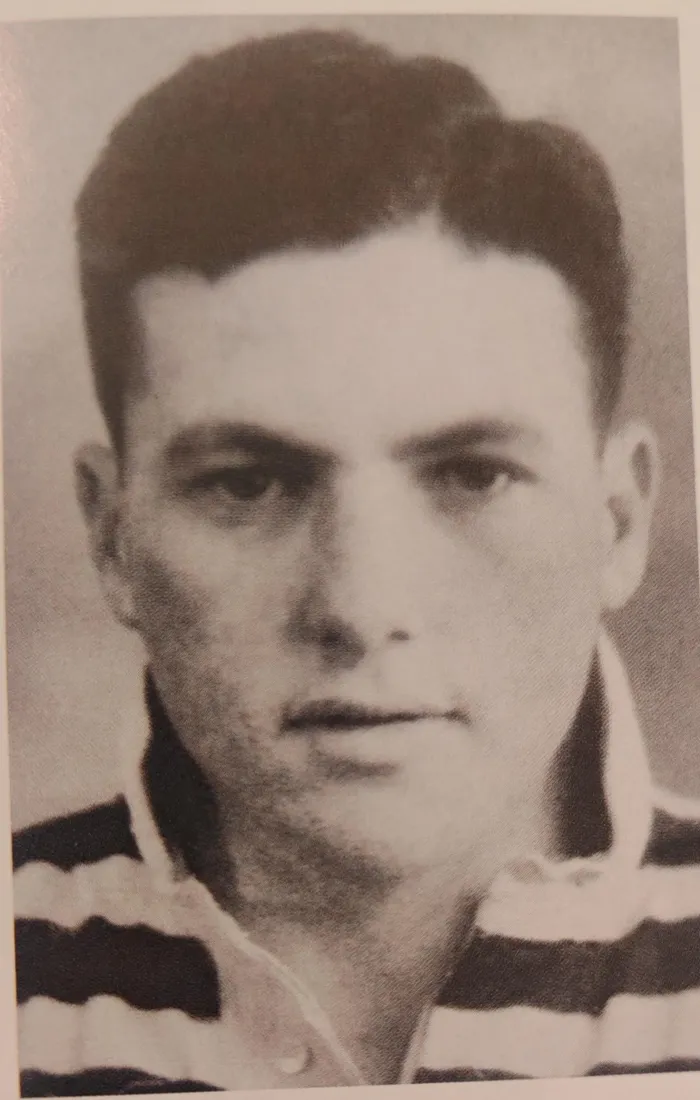

Louis Babrow almost did not play at Eden Park because it was a Jewish holiday. He ended up the star of the show.

Image: Archives

Thousands more stood at the Durban docks to wish the chosen 29 players bon voyage. One of them was the legendary Paul Roos, the captain of the first team to be called the Springboks, the 1906 side that dazzled Britain.

Roos, who had sailed from Cape Town to give his blessing, stood at the quayside and with his famous “soup strainer” moustache twitching with emotion, he told the Boks: “Let the spirit be the spirit of the Charge of the Light Brigade! Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do or die!”

And off they sailed on the appropriately named Ulysses for Australia where they played the provincial teams and two Tests against the Wallabies.

The only games the Boks lost on their 29-match tour were to New South Wales and the All Blacks in the first Test.

A bit of background, and it is amazing how some things have never changed. The Boks had a reputation for playing brutal but boring rugby under kicking machine Bennie Osler.

Osler had retired and the new captain, Philip Nel, decided that the Boks would shed the conservative approach and run the ball.

And this they did under their dapper flyhalf Tony Harris, who was also a flamboyant batsman in the SA cricket team. The Boks swept aside the New Zealand provinces by playing exhilarating rugby, but when they got to the first Test, it had been raining for a week in Wellington and Athletic Park was a swamp.

The Boks lost 13-7.

Tony Harris was a brilliant attacking flyhalf for the Boks.

Image: Archives

For the second Test, in Christchurch, the 21-year-old Harris was given his debut and Craven, who had played flyhalf in the first Test, returned to scrumhalf. The adventurous Boks gifted the All Blacks two intercept tries for a commanding lead at halftime.

The 45 000 Kiwis crammed into Lancaster Park were convinced the world championship was theirs, but the Boks staged a magnificent comeback.

They had to combine courage with skill because two of their players were badly concussed and with no substitutes allowed back then, they played on effectively two men down.

One of them was their prop Boy Louw, who suffered a curious reaction to a blow to the head — a fit of the giggles. He meandered about the field, giggling until Craven found a use for him.

The All Black lock Doug Dalton had been misbehaving in the lineouts and Craven ordered Louw to “sort him out”.

Danie Craven leads out the Boks for the first Test in 1937. Tour captain Philip Nel was injured.

Image: Archives

Except Louw was not mentally equipped to “discipline” Dalton discreetly and descended on the poor bloke in a flurry of fists and boots, most emphatically sorting him out.

This was a no-nonsense era of rugby and the All Blacks exacted revenge, knocking out the wonderfully named Bok flank Ebbo Bastard.

The teams did play some rugby too, and the second half belonged to the Boks, who ran in two excellent tries to win the game and level the series.

The Bok celebrations in their change-room are the stuff of legend. Pat Lyster was so ecstatic that he yelled at star centre Louis Babrow: “Hit me, Louis! Hit me!”So the stocky Babrow did, and Lyster joined Bastard and Louw in dreamland.

Babrow was a gifted centre and a devout Jew but he had a problem —the day of the third Test fell on a special Jewish holiday. He reluctantly declared himself unavailable.

He eventually played after some ingenious reasoning by Craven, who pointed out that while it would indeed be a sacred Jewish holiday in New Zealand on that day, the match would be over by the time it dawned in South Africa, and Babrow was, after all, a South African Jew.

Onwards to a heaving Eden Park where the world crown was at stake. To give context to the great excitement, the 1921 series between these teams in New Zealand had ended 1-1, the 1928 series in South Africa had ended 2-2 and the 1937series was tied at 1-1.

But the 55 000 Aucklanders were soon silenced. Babrow, playing with the zest of a reprieved man, scored two magnificent tries and three more came from his fellow backs.

To describe just one: Craven had invented his famous dive pass and the All Blacks were wary of the distance he could pass. So the Bok backs had worked out a move to deceive them.

When Craven had the ball at his feet at a ruck, he gestured to Harris to move wider. He did this a few times, and the All Blacks’ defence shifted out accordingly until there was a huge gap between their 9 and 10.

When Craven did pass, it was short to blind side wing, Freddie Turner, who had crept into the gap from the touchline. Having sped through, Turner passed to supporting centre Flappie Lochner, who drew the fullback before sending Babrow over in the corner.

The Bok tries were so well crafted that at the final whistle, the crowd rose and clapped the South Africans off the field. In terms of the score, the All Blacks were fortunate that kicker Gerry Brand had suffered a wretched day with the boot, missing four conversions and several penalty attempts.

The score was 17-6 with a try worth only three points at that time. By today’s scoring system, the margin would have been a humiliating 27-6.

This story is an extract from Mike Greenaway’s best-selling book The Fireside Springbok. He also penned Bok to Bok.