Cover of Marion Wallace's well - researched overview of Namibian history.

Image: Supplied

THERE was a time in the 1970s when hardly a week went by without South West Africa (SWA) being in the news. South Africa had exercised control over SWA from 1915 until 1990 when SWA gained independence under its new name of Namibia. Walvis Bay however, remained part of South Africa until 1994 when it was transferred to Namibia which, finally, was united.

Today, South Africans have little interest in their neighbour. Although a number of military histories on the border war in SWA and Angola have been published, few historians have examined South Africa’s 75 years of disputed control of SWA. Even the death in February 2025 of Sam Nujoma, the founding president of Namibia, stirred little debate or reflection in South Africa.

Germany, however, has confronted or been forced to confront its colonial past. SWA became a German colony in 1884 following the (in) famous 1884 Berlin Conference. Britain had annexed Walvis Bay in 1878, but was not opposed to German expansion into SWA.

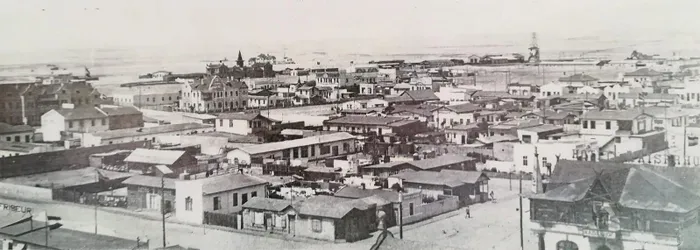

Swakopmund after its capture by South Africa in 1914.

Image: Supplied

Initially, Germany’s commitment to its new colony wavered. As late as 1892, it considered pulling out. This changed in 1894 when Africans were confronted with a very different experience of German domination. Settlers began to arrive in growing numbers and with them, the structures of colonial rule along with roads, railways and harbours.

In central and southern SWA, inhabitants lost not only much of their political power and autonomy, but also land, water and grazing rights. A decade later they took up arms and were answered with genocide.

This grimmest of periods is examined in the re-issue of A History of Namibia by Marian Wallace (Hurst, 2025). First published in 2011, it remains an insightful survey of Namibia, providing the general reader with an authoritative reference book through its detailed examination of existing records. The brief opening chapter (by John Kinahan) covers the current state of archeological research. The main thrust of the book is a study of the period from 1730 until independence in 1990.

In the decade before 1904, the scale and depth of transformation were unprecedented. The independent political power of the African rulers was effectively destroyed. Those who retained a vestige of autonomy only did so through an accommodation with the German authorities.

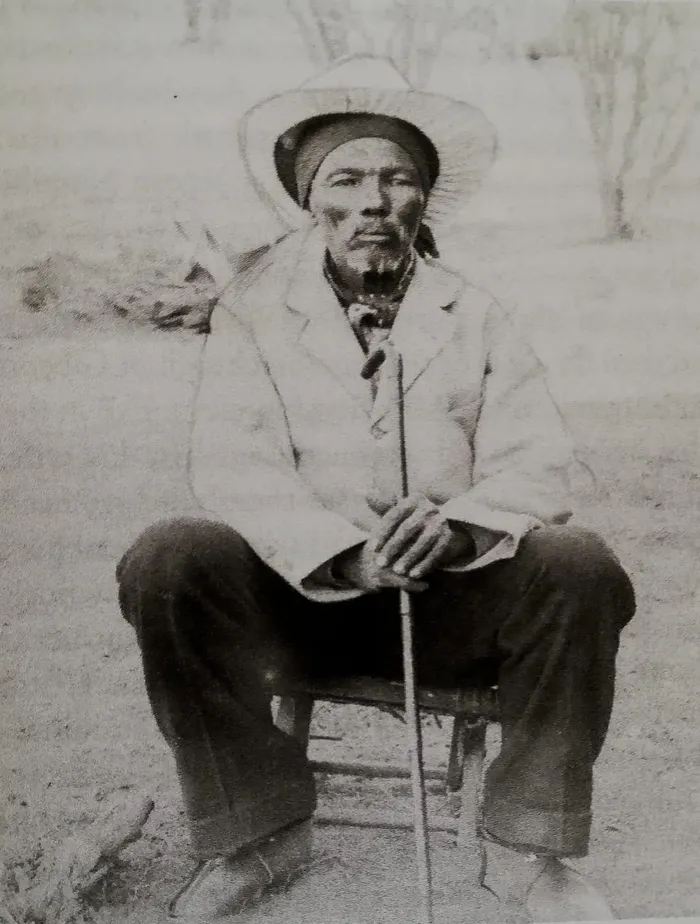

Hendrik Witbooi, one of the most predominant leaders for two decades until his death in 1905. Photo taken circa 1898.

Image: Supplied

One of the most predominant leaders among the Nama people in the South was Hendrik Witbooi, who understood the hidden dangers of forming alliances with the German. As far back as 1890, he warned Samuel Maharero of the Herero people that in surrendering himself to the rule of another, he would realise too late that the Germans would no longer bend to Herero ways.

As an aside, the man with whom Maherero signed a protection treaty was Heinrich Goring, the Imperial Commissioner in SWA and father of the future Nazi leader, Hermann Göring. Witbooi’s letter was prophetic in its accuracy and political acumen.

When the conflict and tension which prevailed in southern and central SWA exploded into wars of resistance against the coloniser in 1904, it was the Herero and Nama people who would be crushed with such brutality that historians today describe it as genocide. Some historians have gone further, arguing that the Namibian genocide planted the seeds for the genocide committed by Third Reich.

Herero women from the Swakopmund camp forced to pull railcars loaded with ammunition.

Image: Supplied

To quell the scale of the uprising, Germany initially despatched 5000 soldiers to the colony, the total would eventually rise to 20 000. At the battle of Ohamakari, the Herero were defeated. Those who could, fled.

It was a death trap: the Herero died in the bush with the mass of their cattle, all dead of thirst. Although there were further military engagements with the Herero, their resistance was broken. General Lothar von Trotha adopted the strategy of occupying the waterholes at the edge of the desert, thus sentencing a people in flight to death from dehydration and starvation.

General Lothar von Trotha who ordered the extermination of the Herero nation in 1904. Representatives of his family went to the Namibian town of Omaruru in 2007 to apologise and express their family's shame over the General's actions.

Image: Supplied

In the south, von Trotha threatened the Nama with the fate of the Herero; his threat did not end the war, although Witbooi was fatally wounded in October 1905. Only on 31 March 1907, could the Germans declare peace. As one author noted, a major European power had been locked in a struggle for years against initially 1 000 to 2 000 and later only a few hundred Nama.

If the period of open conflict was one of great suffering, its immediate aftermath was a time of desperate tragedy. The Germans set up concentration camps into which were herded the defeated survivors. Forced labour and inhuman conditions led to extreme misery and high mortality rates.

Nutrition, housing, clothing and sanitation were woefully inadequate. Female prisoners were habitually taken advantage of by soldiers and white settlers. The camps were also a means of extracting labour of the most arduous type. It was not uncommon to see women compelled to carry heavy iron for construction work. When women collapsed under the load, they were kicked or thrashed and forced to go on.

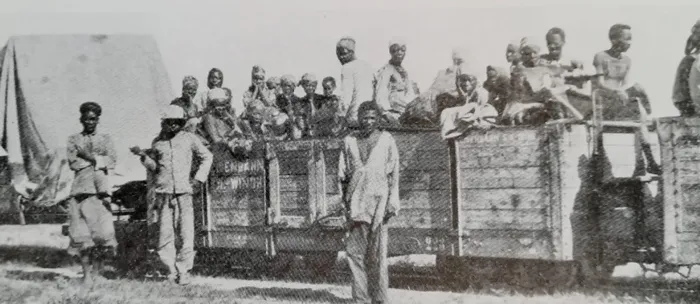

Herero prisoners transported to the Swakopmund concentration camp in cattle trucks, circa 1906.

Image: Supplied

The largest camps were in Windhoek where about 5 000 prisoners were incarcerated (about double the town’s population), the most notorious camp was Shark Island, off Luderitz, where prisoners were so starved that they were nothing but skin and bones. Assessing death rates is difficult, but nearly half died in the camps before they were closed in January 1908.

Nazism was extensively embraced by the German community in SWA in the 1930s, as seen in this open display of Nazi symbols in Luderitz.

Image: Supplied

That the Germans could act with impunity can partly be attributed to the ideology of racial superiority. The nadir was reached when the skulls of prisoners were sent to Germany for research into the nature of racial hierarchy. It was a sinister foretaste of the Nazi obsession with Aryan superiority. More than a century later, these skulls were returned to Namibia, in 2011, 2014, and 2018.

Having military imposed its authority, the Germans sought to maintain it through legislation. The 1907 Native Ordinances enacted control measures, passes, and work contracts, requiring all Africans over the age of six to register with local authorities and carry pass tokens (metal discs). Further legislation compelled Africans to live in separate locations outside white areas and adhere to a night curfew.

German prisoners at Luderitz waiting to embark to POW internment camps in South Africa, June 1915.

Image: Supplied

Most of these measures, with some modifications, were retained when South Africa was granted a “C” mandate to administer SWA after the end of the First World War. On the outbreak of war in 1914, South Africa invaded SWA. Better equipped and with a larger army, South Africa overwhelmed the German Schutztruppe within months. Windhoek was occupied in May 1915, the Germans surrendered on July 9, 1915.

The South African takeover conditioned the history of SWA for the rest of the 20th century, but the German menace was not completely extinguished. With the rise of Nazism and Hitler, it reared its head, posing a potential threat in the 1930s.

Members of the Hitler Youth parade in Luderitz in the 1930s.

Image: Supplied

One of the objectives of the Nazi’s was to regain its colonies. Nazi officials arrived in SWA to promote this message, setting up branches of the party and the Hitler Youth. The South African government responded to this insidious threat by banning both the party and the Hitler Youth in 1934.

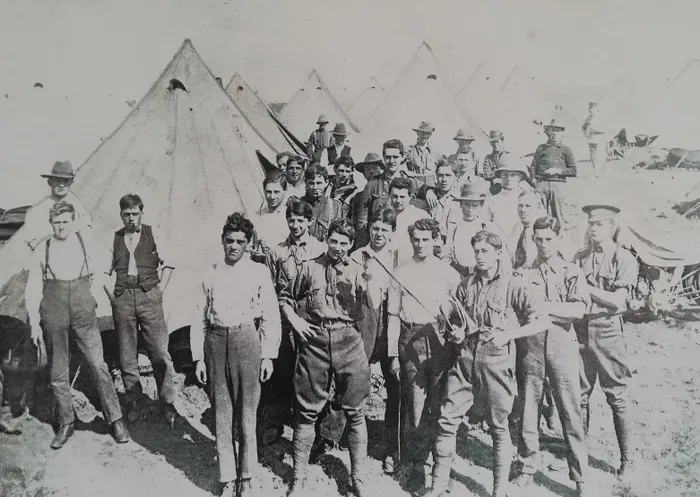

South African soldiers off - loading horses at Swakopmund during the SWA campaign, January 1915.

Image: Supplied

In 2004 when the centenary of the genocide was commemorated in Namibia, Germany asked for forgiveness for “the guilt incurred by the Germans of that time.” Only in 2021 did the German government recognise that the atrocities between 1904 and 1908 amounted to genocide and agreed to give 1.1 billion euros in aid to the communities impacted by the genocide.

South African soldiers at the front during the SWA campaign, 1915. The South African military would remain in SWA until 1990.

Image: Supplied

Colonial rule cast a dark shadow over Namibia for over a century. Such was its impact that it is a marked feature of post-colonial Namibia. Since 2010, the brief period of German colonisation has attracted more attention than the longer period under South African rule. As Marion Wallace observed, the opportunities for research are rich and promising, and it is hoped that historians will take up the challenge.

Related Topics: