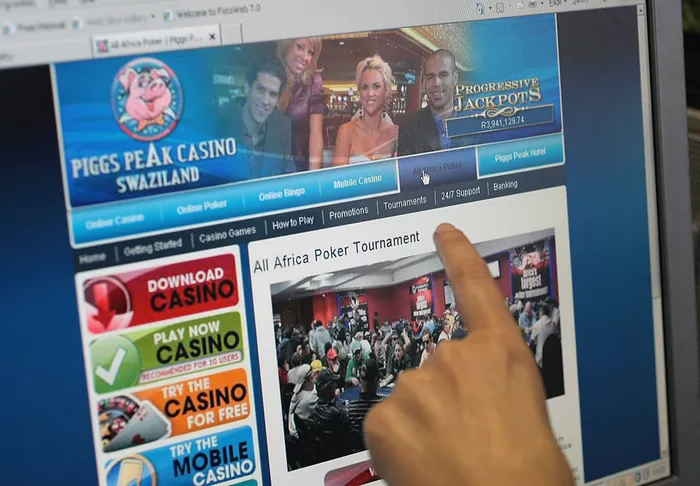

Online gambling has surged disproportionately affecting low-income communities where many people gamble money they should be using to buy essentials.

Image: File

SOUTH Africa stands at a perilous crossroads where the lines between organised crime, gambling syndicates, and political power blur into a dangerous nexus, threatening the very foundations of its democracy.

At the heart of this crisis, Rise Mzansi has sounded the alarm, declaring the country’s gambling epidemic a national emergency, one that is destroying lives while regulators remain passive.

“We are facing a gambling crisis. It is not a minor issue, it is an emergency,” warned Makashule Gana, Rise Mzansi’s National Assembly caucus whip, during the Budget Vote 39 debate on Trade, Industry and Competition. Gana highlighted the plight of vulnerable South Africans, including a “single mother of a 15-year-old boy, terrified that her son will be swallowed by the false promises of gambling”.

The explosive growth of South Africa’s gambling industry, with R1.1 trillion wagered and R60 billion in revenue in 2024, has created fertile ground for criminal syndicates to embed themselves economically and politically. Online gambling, in particular, has surged, disproportionately affecting low-income communities where “many people gamble money they should be using to buy essentials”, Gana noted.

While Rise Mzansi condemned national inaction, the DA exposed critical failures at the provincial level. Michael Waters, DA constituency head for Kempvale, revealed that the Gauteng Gambling Board was severely understaffed, crippling its ability to combat illegal gambling operations.

“The Gauteng Gambling Board has only three law enforcement inspectors instead of the required 10. Seven of the positions are vacant,” Waters said. “All three of these officers have received death threats, obstruction, or intimidation while carrying out their duties and are compelled to work in pairs, which impacts the number of inspections they can carry out.”

This lack of capacity, Waters argues, leaves communities vulnerable to illegal gambling dens, which fuel financial ruin, violence, and broken families. “In the past five years, 1 706 inspections have been conducted on unlicensed operations, yet only 36 referrals have been made to law enforcement agencies,” he said. “The inspectors do not have the authority to shut these places down; they rely on police, who are often absent.”

The gambling industry’s influence extends beyond illegal operations. Wealthy donors linked to gambling, such as billionaire Martin Moshal, have poured R59.5 million into political parties, including the DA and ActionSA, between 2021 and 2023.

While legal, such donations raise concerns about “political party funding mafias” that could sway policy in favour of the industry.

Gana accused the government of neglecting the crisis, pointing to regulatory failures. “Minister Parks Tau, your inaction is part of the problem,” he said. “The National Gambling Board remains incomplete. The National Gambling Policy Council has not met. Meanwhile, gambling operators are running wild, advertising 24/7 with zero accountability.”

The human cost is staggering. Rise Mzansi revealed an almost eight-fold increase in people seeking help for gambling addiction, from 375 in 2020/21 to 2 997 in 2023/24. Gana warned that “even school children are now addicted to gambling,” with “phones coming preloaded with betting apps”.

He issued a blunt demand to the industry: “Develop some shame. Stop flooding our airwaves with adverts. No gambling adverts before 11am. None during breakfast or afternoon drive shows. If the sector fails to self-regulate, this Parliament will regulate you, and it might not be nice. That is not a threat, it is a promise.”

The Global Organised Crime Index ranks South Africa 7th worst globally for organised crime, surpassing countries such as Afghanistan and Russia. These syndicates are “well-armed” and operate with a “high level of violence”, expanding from localised crime into systemic corruption.

While direct proof of a “gambling mafia” controlling political parties remains elusive, the absence of evidence does not mean safety; rather, it highlights the sophistication and opacity of these networks. The Political Party Funding Act, though a step forward, is criticised for loopholes allowing indirect funding, leaving parties vulnerable to undue influence.

Gana vowed that Rise Mzansi would not stop until gambling reforms are “real, enforced, and in the public’s interest”. He said: “No country has ever gambled its way to prosperity.”

The stakes could not be higher. South Africa’s democracy is under siege from well-armed, mafia-style networks exploiting the gambling boom to launder money and buy influence. As one expert warned: “The urgent task of dismantling the extortion economy… is formidable. Yet, overlooking the issue will have repercussions… for the nation at large.”

The time for action is now, before the gambling mafia’s shadow becomes an unbreakable stranglehold on the country’s future.

* Sizwe Dlamini is editor of the Sunday Independent.