How Xi Jinping's leadership is redefining international relations

International Trade

The two-day Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) gathering in the port city of Tianjin drew presidents and prime ministers from across Asia, the Middle East and beyond, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, in what analysts call a direct challenge to US dominance in global affairs.

Image: Supplied

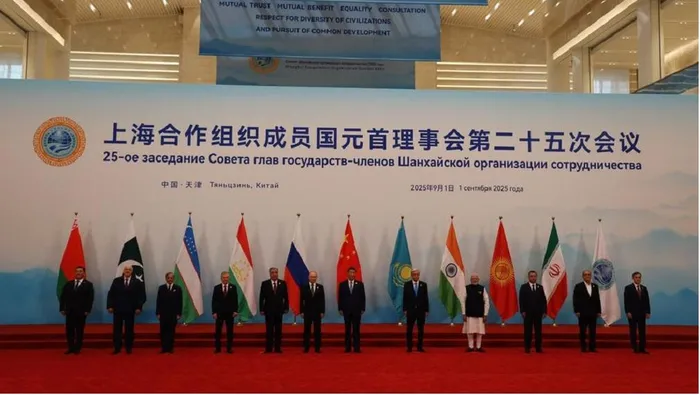

CHINESE President Xi Jinping this week rolled out the red carpet for some 20 world leaders at a security summit in northern China, staging a powerful show of Global South solidarity at a time when US President Donald Trump’s policies have alienated many developing nations.

The two-day Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) gathering in the port city of Tianjin drew presidents and prime ministers from across Asia, the Middle East and beyond, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, in what analysts call a direct challenge to US dominance in global affairs.

By convening such a broad coalition of non-Western leaders, Xi aimed to present a united front of countries that feel underserved by the US-led international order. Chinese officials touted it as the largest SCO meeting yet and proof of what Beijing calls a “new type of international relations” taking shape.

The SCO began two decades ago as a security pact between China, Russia and their Central Asian neighbours; it has since expanded to include India, Pakistan and others, broadening its scope into economic and military cooperation. The message from Tianjin was clear: this was a vision of global cooperation not dictated by Washington.

Xi used the occasion to implicitly rebuke Washington’s approach. In his opening speech, he urged the assembled leaders to “take a clear stand against hegemonism and power politics” and to practice “true multilateralism” — a thinly veiled swipe at the US’s unilateral tactics.

He suggested that Beijing and its partners intend to blaze a different path than the one charted by America in recent decades.

Analysts say Xi’s goal in Tianjin was to illustrate what a world not led by Washington might look like. Eric Olander, editor of the China-Global South Project, noted that months of US pressure on China, Russia and even India have failed to break their solidarity. “Just look at how much BRICS has rattled Donald Trump,” Olander wrote. “That’s precisely what these groups are designed to do.”

That unity was on vivid display at the summit. Cameras captured Putin and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi strolling in together hand-in-hand to join Xi at the opening ceremony — a choreographed show of camaraderie among three of the world’s most influential leaders. The trio laughed together, radiating confidence.

For Putin, long shunned by the West, the warm welcome in China was a diplomatic triumph. It underscored that Moscow is far from isolated in the Global South, despite Washington’s efforts to ostracise it.

This geopolitical realignment is more than just symbolism for countries like South Africa. Africa’s most industrialised economy now finds itself caught in an escalating trade battle with Washington that threatens tens of thousands of jobs — and is pushing Pretoria to seek refuge in the very kind of alternative partnerships on display in Tianjin.

In recent weeks, the US slapped a sweeping 30% tariff on most South African exports as part of Trump’s “America First” trade offensive. The tariffs hit roughly 65% of the goods South Africa ships to the US, dealing a heavy blow to industries from fruit farming to auto manufacturing.

All this comes despite South Africa’s strenuous efforts to preserve its trade relationship with the US President Cyril Ramaphosa even travelled to Washington earlier this year to personally lobby Trump’s team for a reprieve.

During a White House visit in May, he pitched a “framework deal” to address American complaints: Pretoria offered to buy large quantities of US liquefied natural gas over the next decade and invest billions of dollars in American industries, while also agreeing to limit South African steel and aluminium exports to the US.

Even these major concessions were not enough to placate the White House. That failure left Pretoria frustrated and exposed. South African officials insist their country poses no real threat to the US economy and say they will keep trying to negotiate — but in the meantime, they have little choice but to seek relief elsewhere.

Almost immediately after the tariffs hit, South African negotiators clinched a landmark export deal with China to help absorb some of the pain. Beijing agreed to open its market to five types of South African fruit — including peaches, plums and nectarines — an unusually broad farm trade agreement that officials say could be a game changer for local growers.

“China, with its 1.4 billion people, has too many mouths to feed and a lot of demand for our products,” a South African agriculture official said this week, underscoring the huge opportunity in the East. It was the first time China approved multiple new import categories from South Africa at once — a gesture of goodwill as the country scrambles to find new buyers for its goods.

Officials say they have put the country on a “fast track” to diversify export markets and reduce reliance on any single partner. They are rolling out support programs to help local firms find customers across Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and courting neighbouring African countries as buyers of South African wine and manufactured goods.

The expanding BRICS partnership is a crucial pillar of this strategy. As the only African member of BRICS, which also includes Brazil, Russia, India, and China, South Africa is leveraging those ties for both trade and investment.

The BRICS’ New Development Bank, for instance, has approved a 7 billion rand ($400 million) loan to help upgrade South Africa’s highways. Such funding offers a welcome alternative as Western aid stagnates.

For South Africa, turning toward the East is increasingly a matter of necessity rather than ideology. Trump’s tariff salvos may have been aimed at pressuring US rivals, but they have also pushed a partner like South Africa closer to China and other rising powers.

As Xi’s summit in Tianjin showed, the Global South is positioning itself as a viable alternative power centre, one where developing nations support each other when relations with the West fray.

Whether this marks the dawn of a post-American order is still uncertain. But one thing is clear: as Washington raises walls, countries like South Africa are finding open doors among their fellow emerging nations.

* Dr Eric Hamm is a professor of political science and a strategic researcher. The views expressed here are his own.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media, or IOL.