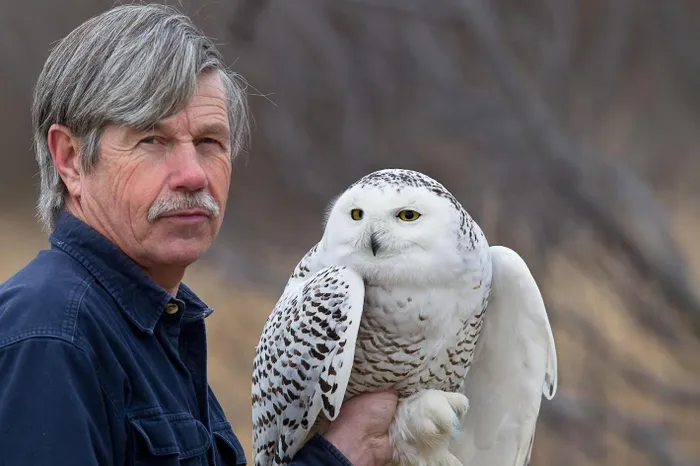

Norman Smith with an Arctic Snowy Owl.

Image: Supplied

Andrea Sachs

Every winter, Arctic snowy owls fly thousands of miles south to Boston Logan International Airport. And every season, Norman Smith drives less than an hour to try to snatch them up.

“I’ve seen a plane taxiing down the runway and the people looking out and seeing me with a bird,” said Smith, 73. “They’re like, ‘What’s that? What are you doing?’”

Known as the “owl man of Logan airport,” the raptor researcher has caught and released into the wild more than 900 snowy owls that decided Boston Logan was their Boca Raton. When the temperature begins to drop, the Arctic raptors, especially the juveniles, migrate to relatively warmer climates. Many choose the airport, home to the largest known concentration of snowy owls in New England. The East Boston site also sits along the Atlantic Flyway, a superhighway for migratory birds that stretches from Greenland to Florida.

With the congested airspace and constant rumble of jets, the airport is hardly a tranquil bird sanctuary. But Smith said the terrain resembles the Arctic tundra. It’s open, flat and barren, with water on three sides and plenty to eat, including waterfowl and small mammals.

The airfield is also a dangerous place to alight. A collision between a plane and an owl can end badly for both types of fliers.

“The importance of Norm coming in is that he helps us take out a significant threat to aviation safety, which is a large, dense-bodied bird on the airfield,” said Jeff Turner, the airport facilities supervisor for the Massachusetts Port Authority.

In 1981, Smith sent a letter to his home airport, asking whether he could study the visiting raptors. He offered to humanely trap the owls from October to spring, or whenever the last bird decided to return home. After checking their vitals, conducting a few tests and banding their legs, he would release them farther afield, such as from Cape Cod or the North Shore.

“If it was early in the season, you’d want to move them south of the airport, because the birds were generally heading south,” said Raymond MacDonald, a wildlife photographer who has been collaborating with Smith for 15 years. “If you released them north of Logan, they might run into Logan again.”

Smith started that fall and has not stopped.

Several times a month, Smith will drive to Boston Logan, where he has a high security clearance. In the back of his truck, a bow trap rattles, and the live mice don’t make a peep. (No animals, including the bait, are harmed in the process, he says.)

He typically catches 10 to 15 snowy owls a year, plus several other birds of prey, such as short-eared owls, peregrine falcons, red-tailed hawks and harriers. He set a personal record in the 2013-2014 season, capturing 14 snowy owls in one day and 121 over the winter. In late March, it was 15.

“They might be just sitting there, they might be hiding or they might be sleeping,” Smith said of his targets. “They could be out on the salt marsh, roosting or feeding on a duck or a rabbit. Obviously, those birds you’re not going to catch, because the bird has to be hungry.”

The Boston-area native, who started working at Mass Audubon as a teenager and recently retired as director of its Blue Hills Trailside Museum, is a preeminent authority on snowy owls. He was the subject of a recent award-winning short documentary film by local filmmaker Anna Miller, called “The Snowy Owls of Logan Airport.”

Through tagging, satellite telemetry and field work, he has made numerous discoveries about the species’ life expectancy, vision, migratory routes and feeding habits. He was a pioneer in bird tracking, attaching transmitters to wintering snowy owls and determining that the animals successfully complete the 3,000-mile odyssey to the Arctic.

But not all of them do.

“I was out there one time, and a snowy owl was sucked into a Learjet engine. It blew the engine, and the plane had to turn around and come back,” Smith said. “That’s the reason why we catch them and move them from the airport.”

Smith said some people have suggested he leave the snowy owls alone. He shrugs them off.

“That’s not good for the owl,” he said, “and it certainly isn’t good for the plane.”

Boston Logan is haunted by the specter of a 1960 bird strike that ranks as the deadliest of its kind. In October of that year, a flock of starlings caused Eastern Airlines Flight 375 to plunge into Winthrop Bay minutes after takeoff. Of the 72 passengers and flight crew members on board, 10 survived.

More often than not, bird strikes are not life-threatening to airplane passengers, but they can be harrowing. One of the most famous nonfatal incidents occurred in New York in 2009, when a US Airways plane flew into a flock of Canada geese. Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger III safely landed the aircraft on the Hudson River.

Wildlife strikes are on the rise, according to the Federal Aviation Administration’s most recent and complete data.

In 2023, the agency recorded 19,603 run-ins in the United States, a 14 percent increase from the previous year’s 17,205 collisions. Around the world, wildlife accidents involving civilian and military aircraft have killed more than 491 people and destroyed more than 350 aircraft between 1988 and 2023. Domestically, the numbers are 76 and 126, respectively.

During roughly the same period, nearly 800 species were involved, including 651 bird species, such as black and turkey vultures, gulls, brown and white pelicans, trumpeter swans, American kestrels, bald eagles, and snowy owls. Among birds, the FAA said, waterfowl, raptors and gulls cause the greatest amount of damage.

Airports employ a battalion of tactics to deter birds and mammals from tangling with aircraft operations. Not all of the strategies are well-received.

In 2013, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey instructed its airports to shoot any snowy owls on the premises, a legal method despite protections from the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Workers at JFK International killed three snowy owls, unleashing a public outcry. The episode also spurred Turner, who was a Department of Agriculture biologist at the time, and Smith to create a USDA-accepted protocol for airport wildlife practices dealing with raptors.

On a late March morning, the Blue Hills Trailside Museum in Milton was still in winter’s grip. Smith wore a blue Mass Audubon hoodie, baggy black jeans and scuffed leather hiking boots. With his snowbank of hair and intense gaze, he resembled a snowy owl. When he smiled, his bushy white mustache quivered like feathers in the wind.

I followed him into the small museum and to a glass case containing a pair of taxidermied snowy owls. Smith launched into a lesson about the birds - their size and coloring, courtship rituals, breeding habits, and taste for lemmings.

In addition to his research, the grandfather of six is an educator. One of his primary goals, he said, is to inspire people, especially young ones, and help them “better understand, appreciate and care for this world in which we live.”

Back outside, two snowy owls in an enclosure coolly regarded us as Smith recounted their backstories. Both were airport rescues. The female bird had been sitting on a snow-melting machine at Boston Logan, and the heat caused irreparable damage to her feathers.

“This bird is not going to find its way back to the Arctic,” Smith said.

The other snowy owl, a male, was hit by a plane at Baltimore-Washington International Marshall Airport and suffered a broken shoulder. It will never soar again, either.

The tour ended at his truck, a hybrid classroom and mobile office. Smith keeps snowy owl specimens in his vehicle, as well as the bow trap he uses at the airport. On a hard patch of dirt, he demonstrated the contraption, which he jury-rigged with a fishing pole and long line. The box containing the bait was a miniature version of a great-white-shark cage: The prey can see the meal but not taste it.

When choosing a location to set up a trap, he coordinates with the airport staff to avoid active runways. He doesn’t want an owl to dash across the tarmac and get slammed by oncoming traffic.

“There have been cases [at other facilities] where they try to chase the snowy owls off the airfield and the birds get upset and are looking at the vehicle that’s trying to chase them,” Smith said. “They’re not looking for the plane, and then they get hit by a plane.”

In the field, he camouflages himself in his vehicle, sometimes peering at the owl through binoculars or a night vision scope. As soon as an unsuspecting bird lands on the trap, he yanks the fishing rod, releasing the net over the catch. He will then drive over to the apparatus, seize the bird by its feet and stash it in a carrier.

“You grab it before it grabs you,” he said.

On Monday, he received a tip from a birdwatcher. He dashed over to the airport but didn’t see the reported owl.

His season tally remained 15. | Washington Post