People jump off of the American Legion Memorial Bridge, known as Jaws Bridge, at Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard, on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post

Andrea Sachs

Megan Wright stood on “Jaws Bridge” as people around her leaped through the air and splashed in the water below. She peered over the railing, watching them swim safely to shore. Her partner cajoled her to jump. She shook her head, an emphatic no.

Fifty years ago, the summer blockbuster about a homicidal shark warned millions of moviegoers, “You’ll never go in the water again.” For Universal Studios, it was a provocative tagline. For “Jaws” fans like Wright, a barber from Pittsburgh, it was a prophecy.

“‘Jaws’ changed my life forever. It made me afraid of the ocean, afraid of sharks,” said Wright, 47, who holds the permissive uncle who took her to see the movie responsible for her childhood phobia. “I watch these people go out swimming, and I just can’t.”

But their galeophobia (fear of sharks) doesn’t hinder them from pursuing “Jaws” by land. Many fans will cross waters crawling with apex predators to visit the island where, in 1974, a young, inexperienced Steven Spielberg filmed a surprise hit that broke records and won awards. For the movie’s 50th anniversary over the weekend of June 20, hundreds of people traveled by plane, ferry and private boat to reminisce about their first screening, tour the film locations, hobnob with some of the actors and extras, and dare themselves to go in the water.

“The shark did not scare me,” said Cape Cod resident Rose-Emily Calo, who watched the movie with girlfriends when she was 12 years old. “We now have a boat, and we know there are sharks in the water. But it doesn’t matter. I lived in Colombia. There are other things to be afraid of.”

Seven miles off the Massachusetts coast, Martha’s Vineyard is one of the purest examples of set-jetting, the travel trend based on visiting movie or TV show sites. Since Spielberg landed on Martha’s Vineyard’s shores, little has changed, at least aesthetically. The timeless island and its fictional counterpart, Amity Island, are almost twinsies, despite the age gap.

“People on ‘Jaws’ pilgrimages can walk through these locations and really feel like they’re on the movie set,” said Mike Currid, a summer resident who has been leading “Jaws” walking tours for 15 years. “We’re afforded that luxury because of our whaling history and because of the buildings we have protected for some 200, 250, 350 years. That protects our ‘Jaws’ history, too.”

The locals hired as extras or assistants also returned to island life after their Hollywood minute. They are now the police chief of Oak Bluffs (Jonathan Searle, the delinquent kid who wore a cardboard fin); a real estate mogul who holds court on a bench by Scoops Ice Cream in Edgartown (Geno Courtney, Town Hall scene); and a real estate agent who shows multimillion-dollar homes (Rene Ben Davis, young sailor in the estuary).

“Because Steven and his team kept things so close to the island, those same people that are still with us are still telling those tales,” said Erica Ashton, executive director of Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce. “The islanders are really proud that the movie put Martha’s Vineyard on the map.”

Dan and Steve Perrault pose for a photo during the “Jaws” 50th anniversary event at Martha’s Vineyard Museum on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post

Martha’s Vineyard almost wasn’t Amity Island; Nantucket was. During a scouting mission, production designer Joe Alves was headed to that other Massachusetts island when a snowstorm suspended ferry service. The boat to the Vineyard was still running, however, and he boarded it.

Though “Jaws” author Peter Benchley had previously dismissed the island, reportedly saying “I don’t think there’s anything there,” according to a MV Museum exhibit about the film, Alves found everything there.

“Martha’s Vineyard had so many different sites - beautiful Edgartown with its stately buildings, and Menemsha, with its grasslands, ponds and beautiful views,” said Wendy Benchley, the author’s widow, who attended the recent festivities and summers here. “Plus, it had the 25-foot ledge that allowed them to look like they were out on the open ocean when they actually were in 25 feet of water.”

In May 1974, Spielberg and his film crew moved to the island for what was supposed to be a 55-day shoot. Many of the key players, such as film editor Verna Fields and Roy Scheider (police chief Martin Brody), stayed at the Harbor View Hotel in Edgartown. For the 50th anniversary, the luxury property, whose rates often exceed $1,000 a night during high season, was booked solid.

The islanders wanted Spielberg to wrap before the summer crowds started to arrive, a demand seemingly plucked from the screenplay - Mayor Vaughn to Brody: “I’m only trying to say that Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars.” Weather disruptions, mechanical shark malfunctions, Robert Shaw’s boozy spells and other mishaps famously busted the budget by $5.5 million, lengthened the production time by more than 100 days and frayed already raw nerves.

“One of our favorite stories is about a spontaneous food fight supposedly between Steven Spielberg, Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss that took place in what is now Bettini the restaurant,” said Jean Wong, director of marketing at the Harbor View Hotel. “Some say that it was to release tension because the movie went way over budget, way over time and people were really getting tense and stressed, so they just started flinging food at each other.”

Half a century later, the only projectiles flying through the air were seagulls and movie quips.

“The beaches are open,” a visitor at the MV Museum called out to a gent dressed in the mayor’s signature blue blazer with anchors.

In Oak Bluffs, Heidi Robinson, a local whose mother worked on a barge that towed Bruce the shark, walked the docks hoisting Chrissie’s severed arm like a specter. On her own left hand, she wore replicas of the victim’s rings that the original jeweler, CB Stark, was selling at its two Vineyard stores.

Her friend from Connecticut was carrying a shark costume. She hoped the outfit would stand out among the sea of “Jaws” T-shirts, shark sunglasses and blue watch caps, and entice Dreyfuss to pose for a photo with his catch.

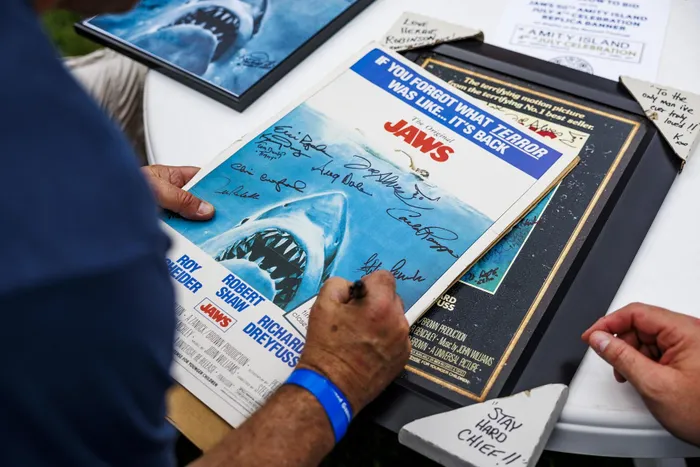

Peter Robb, an extra on the set of “Jaws,” signs autographs during the 50th anniversary event at Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post

Timed to the anniversary, the chamber of commerce created a film site map in partnership with the Massachusetts Film Office. It features more than two dozen spots, including South Beach, the setting of the opening bonfire scene and the discovery of Chrissie’s arm; the Chappaquiddick “Chappy” Ferry, where the mayor and Brody face off over opening the beaches on July Fourth; and State Beach, where Alex Kintner met his maker while floating on a raft.

The island also teamed up with SetJetters, a travel app for movie and TV buffs. The official app for the 50th anniversary features 27 sites. Users can compare Vineyard summer of 1974 to Vineyard summer of 2025. Beside the cars and coiffures, not much has changed.

“If you want to get a sense of what Martha’s Vineyard was like back then, watch the movie,” said Mark Trude, a superfan who divides his time between Northern Virginia and Edgartown. “But the thing is, it’s still the same.”

Though Martha’s Vineyard experienced a “Jaws” effect, it has not attracted the same level of fandom as Iceland and Dubrovnik (“Game of Thrones”), Thailand (“The Beach” and “White Lotus”) or Sicily (“White Lotus” again), all of which are battling overtourism.

After the film’s release on June 20, 1975, Wong said more people came to the island the following summer. But the movie was not their primary reason for visiting.

Guests gather for the “Jaws” 50th anniversary event at the Wharf Pub in Edgartown, Martha's Vineyard, in Massachusetts on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post

“The majority of the guests aren’t coming because ‘Jaws’ was filmed here 50 years ago,” Wong said. “But when they get here, they love to hear the stories and go on the ‘Jaws’ tours. They really get a kick out of seeing where it was filmed and hearing about it.”

Edgartown town administrator James Hagerty identified three “major milestones” that have reshaped the island’s dynamic and vibe. One is “Jaws”; the other two are vacationing presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. (In 2019, the Obamas purchased their rental property.)

Like many islanders, Hagerty, 42, has a personal connection to the film. Robert Nevin, his grandfather, starred in the movie as the medical examiner, a natural role for the real-life physician. As a kid, Hagerty saw his grandfather on the big screen at the Edgartown movie theater, which regularly screens the movie. (The Drive-In at the YMCA will show it twice this summer.)

Hagerty can pick out “Jaws” tourists based on where they are pointing their cameras. If they come inside Town Hall, he will show them the meeting room and clock that appeared in the film and direct them to the Chappie Ferry, which putters 527 feet from shore to shore.

“Easily a couple of times a month in the summer, I’ll see people who are solely going to look at the landmarks for ‘Jaws,’” Hagerty said. “I don’t think that interest has ever waned.”

Jim O’Hern poses for a photo in a faux shark cage at the Wharf Pub during the “Jaws” 50th anniversary event at Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard, on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post

Last year, the Edgartown board of trade kicked off Amity Week, which Ashton said will become an annual tradition. This year, it coincided with the anniversary event, transforming the island into JawsCon for five days.

Around the island, businesses decorated their buildings with images of sharks, “No Swimming Hazardous Area” signs and a raft with a blood-spattered, shark-bite-size hole. Stores sold commemorative souvenirs, including T-shirts, sunglasses, hors d’oeuvres platters, strings of lights, books, pint glasses and limited-edition Vineyard Vines apparel. Bars concocted specialty cocktails, such as the Shark Bite at the Harbor View Hotel and the Alex Kintner at Rockfish - potent sips that could subdue a shark. Mad Martha’s filled cups and cones with Shark Attack, a mix of blue vanilla ice cream, white chocolate chunks and raspberry puree.

“Martha’s Vineyard has been partially responsible for the legacy of one of the greatest movies of all times,” said Guy Masterson, director of the London West End and Broadway show, “The Shark Is Broken,” which will open at the Martha’s Vineyard Performing Arts Center in Oak Bluffs on July 5.

At the MV Museum in Vineyard Haven, visitors lined up to see the “Jaws at 50: A Deeper Dive” exhibit, which runs through Sept. 7. On Reunion Day, held on the museum grounds, locals shared their memories from that summer when they unexpectedly became part of cinematic history.

“I was a hippie, and we didn’t put our kids in bathing suits,” said Cathy Weiss, who earned $40 a day to scramble out of the blood-soaked ocean with her naked daughter, Beka.

Weiss, a retired teacher, said Spielberg asked her to drop Beka during the stampede and scream, “My baby!” She declined, even though she would have made $50 more and nabbed a speaking part.

In Oak Bluffs, crowds gathered around slip number 64. They craned their necks to peer inside a replica of the Orca and swarmed Michael Sterling, the English boat builder and Quint look-alike who had turned a 1964 lobster boat into the film’s legendary shark-fishing vessel.

“I need to get onboard the Orca,” said Sterling, recalling the ambitions of his 7-year-old self. “So the only way to do that was to build one for myself.”

It took nine years, and a harrowing drive from his home in Florida, but Sterling finally delivered his paean to “Jaws.” Since arriving on the Vineyard, however, the boat has been beset by problems. Fortunately, a shark attacking his Orca isn’t one of them.

A beach house on Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard, on June 22.

Image: Adam Glanzman/For The Washington Post