He knows he was adopted from South Korea. The rest is a troubling mystery

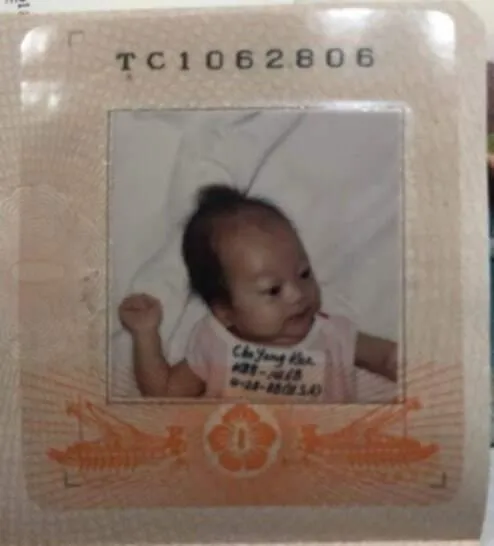

A baby photo of Aaron Grzegorczyk, born Cho Yong-kee and an adoptee from South Korea, in his adoption file.

Image: Family photo

Kelly Kasulis Cho

For most of his life, Aaron Grzegorczyk believed that his birth name was Cho Yong-kee. He thought he was born on April 28, 1988, in a clinic in Anyang, South Korea, about 11 miles south of Seoul. He was told that his mother, a 19-year-old unwed woman, had abandoned him a day after giving birth to him. In an initial physical exam, he was recorded as “cute and alert.”

Less than five months later, he arrived into the arms of his adoptive Polish American parents in Bay City, Michigan. He was their first child, sensitive and artistic, and his birth mother had surrendered him so that he could have, as his adoption papers put it, “an optimum future.”

Grzegorczyk never questioned this story until this past March. That’s when his friend sent him an article detailing the South Korean government’s admission to five decades of adoption fraud.

“I was reading it and I was just like, jaw open,” Grzegorczyk said. “I had absolutely no idea about any of this.”

Immediately, he started digging into his past.

South Korea’s adoption ‘industry’

Earlier this year, a South Korean government-appointed, independent investigative commission released a damning report that for the first time admitted the country had allowed human rights abuses to occur in what it criticized as a decades-long “profit-driven” adoption “industry.”

An examination of dozens of cases between 1964 and 1999 found that some children were taken without their biological parents’ consent, while others were given false birth names and fake background stories before being sent abroad for steep adoption fees. Some were sent without legally valid documents or with little to no screening of the adoptive family, and agencies often scurried to fulfill orders or quotas in what the report called the “mass exportation of children to meet demand.”

“The long-standing intercountry adoption practices represent a failure of the government to uphold its responsibility to protect the fundamental human rights of its citizens,” South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission said.

The TRC’s conclusions were based on a partial review of 367 cases submitted by adoptees across 11 countries. It’s unclear how many of the more than 200,000 Korean children estimated to have been adopted internationally since the end of the Korean War were sent abroad under unlawful pretenses, but experts say bad practices by adoption agencies were widespread. In some cases, the birth parents were lied to and told their child had died shortly after delivery.

“We have not seen one case where there is not an issue,” said Boon Young Han, one of several adoptees from Denmark who banded together as the Danish Korean Rights Group and successfully campaigned for the South Korean government to launch its investigation. Her organization has meticulously investigated more than 2,000 cases.

Grzegorczyk with his adoptive family in Michigan.

Image: Family photo

An ‘existential crisis’

For Grzegorczyk, the recent news has thrown his entire life course into question. He was in his early teens when his adoptive mother told him that his birth mother had abandoned him - a moment he now refers to as his “first existential crisis.”

“That was the very first mental and emotional issue that I ever confronted in my life,” he said.

South Korea had just risen out of widespread postwar poverty and was in the throes of its decades-long struggle for democratization when Grzegorczyk was born. The country had already massively transformed its economy, but it was not the Group of 20 nation it is today.

Grzegorczyk grew up feeling out of place in a predominantly White community, he said, and began having behavioral issues in his early teens. He attended graphic design college in 2006, but dropped out amid the 2008 financial crisis, fearing his degree would be useless for getting a job. He then worked for years as an emergency medical technician - a job so “rough” that he was eventually diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, he said.

Grzegorczyk began suffering from substance abuse issues. He quit his emergency responder career, which paid close to minimum wage, and resorted to selling drugs, he said. He got in trouble with the law and spent a few stints in jail.

“I can’t say whether or not my adoptive parents are proud of how I turned out,” he said. “ … I’ve made the most of my life despite a lot of hardships, most of which I did bring on myself.”

He turned his life around in 2019, he said, when he found out he was expecting a child. He got sober and started a roofing apprenticeship.

“I finally got into a place where, I wouldn’t call myself happy, but I am for the most part at peace,” he said during a Zoom call in April. “Up until about five days ago, when I heard about all of this,” he added, his smile giving way to tears.

Grzegorczyk with his daughter, Isla.

Image: Family photo

Dizzying quests for the truth

For years, activists and adoptees have criticized adoption agencies in South Korea for being slow or outright uncooperative in sharing their adoption records. Several adoptees told The Washington Post that they’ve been searching for their complete records for years, bogged down in the bureaucracy of working with adoption agencies in South Korea as well as filing Freedom of Information Act requests in their home states.

“The documents are not just a piece of paper,” Han said. “That is our one and only clue, our one and only opportunity, to trace back our original identity.”

South Korea recently ordered all adoption agencies to turn their files over to a government office called the National Center for the Rights of the Child, starting in July. The change could standardize birth family searches, Han said, but she also fears some documents will get lost in the transfer. Meanwhile, politicians are debating whether they’ll investigate more adoption cases.

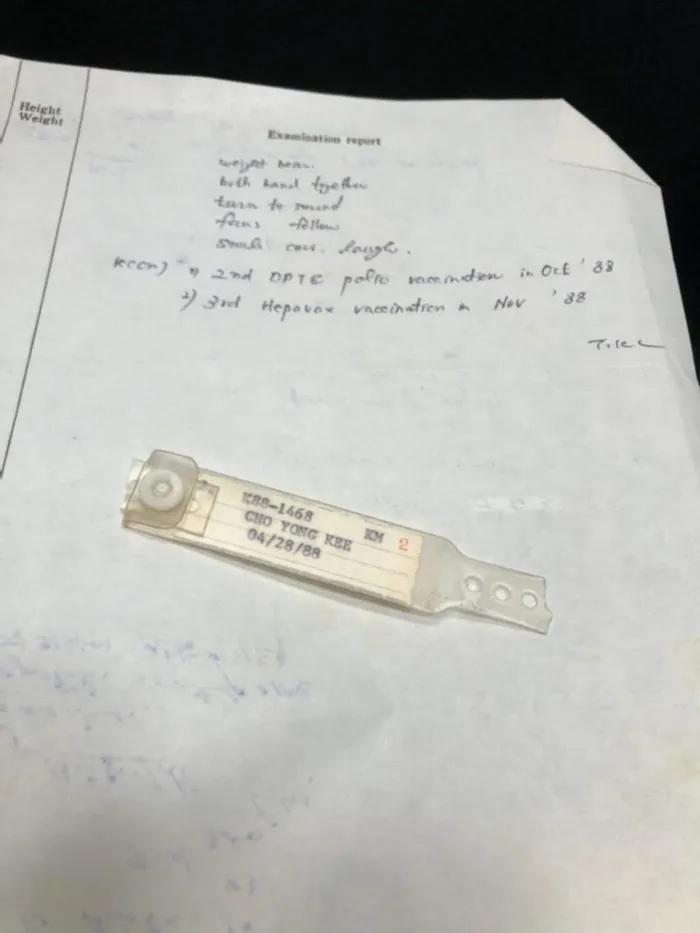

In Grzegorczyk’s case, the paperwork his adoptive mother saved for him raises some red flags: The file does not include a police report detailing his abandonment, nor a relinquishment consent form signed by a birth parent. There is no name or address for the clinic he was supposedly left at as a newborn, and several fields on his forms are left blank. His family origin is also listed as “Hanyang,” a placeholder term referring to Seoul.

“If it says ‘Hanyang’ in the document, then you know the name is falsified. It’s incorrect,” Han said. “It’s like saying someone comes from Disneyland,” she added.

A page from the adoption file of Grzegorczyk, 37, born Cho Yong-kee on April 28, 1988, in Anyang, South Korea, with an identification bracelet that had been attached to him as a baby.

Image: Family photo

Hope for reunion

In mid-April, Grzegorczyk faced another twist: A worker at his adoption agency told him that she had spoken by phone with his purported birth mother, whom the employee said was “happy to keep in touch” with him and had been “waiting for a long time.” The worker asked Grzegorczyk to write her an introduction letter, which the agency confirmed it translated and sent days later. In the letter, he spoke fondly of his 5-year-old daughter, Isla, his brother and his sister - also a Korean adoptee - and his young nieces.

“I never tried to look for you because I didn’t think you wanted to be found,” he wrote. ” … I have so much more to say and questions that I would like to ask you. But I don’t want to overwhelm you. I was so happy to hear that you wanted to talk to me.”

But Grzegorczyk hasn’t heard anything from his mother since. The adoption agency worker told him that his case will be turned over to the government office that is taking over adoptee records in July, and said his mother never responded to a second phone call.

He seemed resigned, asking the worker to give his contact information to her.

Driving his car back from Detroit in the middle of the night in mid-May, he looked forlorn in a video message, masking his disappointment in between jokes and grins.

“I never planned on hearing anything from anybody in the first place, my whole life,” he said, appearing to try to cheer himself up.

“Maybe my paperwork wasn’t made up,” he added. “Let’s say it is 100 percent true. At the very least, I would understand.” | The Washington Post