Lost work by Virginia Woolf to be published

Virginia Woolf's writings collected in the "friendship gallery" were possibly never intended for publication, but to amuse her friends.

Image: Supplied

Sophia Nguyen

Long before “A Room of One’s Own,” a 25-year-old Virginia Woolf wrote a trio of fairy tales about a woman named Violet, plain and very tall, who loved literature, kept a magic garden and built “a cottage of one’s own.”

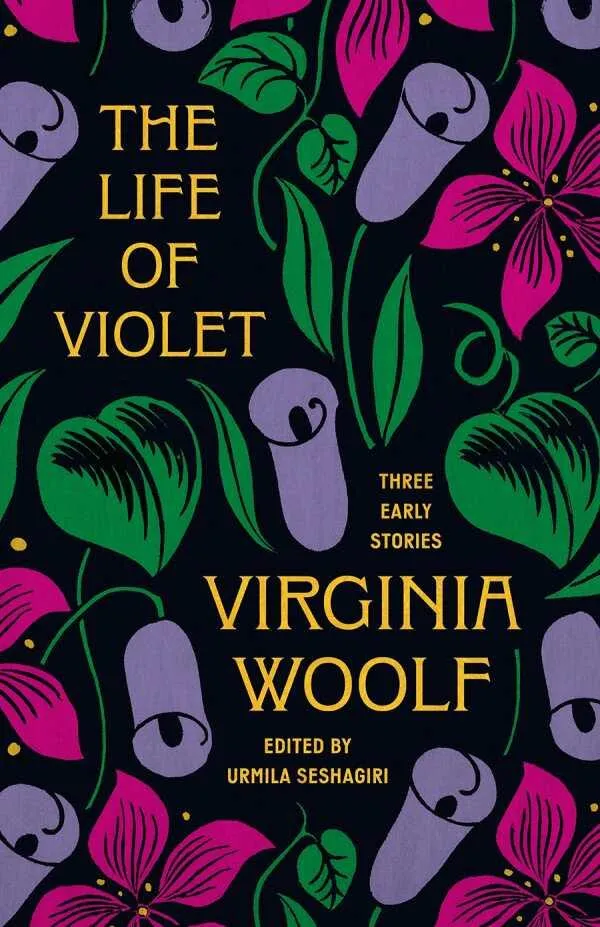

This early experimental fiction, rediscovered in 2018, is now being published for the first time by Princeton University Press. Titled “The Life of Violet” and edited by Urmila Seshagiri, the book was released on Tuesday.

Seshagiri, a professor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, stumbled on the stories while conducting research for a new edition of Woolf’s “A Sketch of the Past,” an uncompleted memoir. An archivist at Longleat House, a historic estate in Wiltshire, England, casually mentioned that they had an original typed manuscript of a text known as “Friendships Gallery,” with Woolf’s handwriting on its pages. Seshagiri’s curiosity was piqued: The New York Public Library, which has the largest collection of Woolf’s papers, was thought to hold the original manuscript of “Friendships Gallery.”

“No one takes ‘Friendships Gallery’ seriously,” Seshagiri said; most scholars have considered the work a hastily drafted inside joke, written for the entertainment of Woolf’s inner circle, in tribute to her friend Mary Violet Dickinson. Though there was no indication she intended for the stories to be published, the NYPL version was lovingly typed in purple ink and bound in purple leather, and contained handwritten notes from both the author and Dickinson. The text of the stories, first appearing in a 1979 scholarly journal, was considered so marginal that it was left out of collections of Woolf’s short fiction.

The book released this week of Virginia Woolf's recently discovered writing.

Image: supplied

Woolf’s shorter works have generally gotten less attention than her novels, Bryony Randall, a University of Glasgow professor, wrote in an email, and “this one in particular probably has attracted even less attention, because its apparently unfinished status and its strange generic instability means scholars might be cautious about making claims about it.”

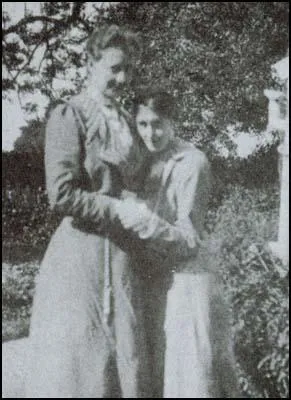

The real-life Violet Dickinson cut an unconventional figure: Aristocratic and never-married, standing 6 feet 2 inches, she cultivated a vibrant social and literary life. She was one of Woolf’s chief correspondents during the author’s young adulthood and, during Woolf’s mental breakdown in 1904, housed and tended her. Dickinson also encouraged Woolf’s literary ambitions, giving her a large inkwell and introducing her to her first newspaper editor. Some see Dickinson as primarily a maternal figure for Woolf, who called their relationship a “romantic friendship”; others, pointing to the erotic language in their letters, maintain that Dickinson was Woolf’s first love.

Violet Dickinson and Virginia Woolf in 1902.

Image: Supplied

Seshagiri considers the stories in this collection “kind of a singularity” in Woolf’s writing. The prose is unusually Victorian in its sensibility and narrative form, and features overtly magical elements, like monsters and flying princesses. “She doesn’t do anything that resembles this later.”

After the NYPL shared a scan of its version with Longleat, the archivist confirmed that the manuscript in the Longleat collections was different, with more recent edits. “And I’m just passing out from anticipation,” Seshagiri remembered. But thanks to the pandemic and the vagaries of international copyright law, it took years before she could see it for herself.

When she did, Seshagiri was struck by the surprisingly polished prose, clearly pored over by the author. Woolf had obviously paid close attention to the structure of the work, from the smallest considerations of page layout to tweaks that made the language longer, lyrical, more flowing - and at times, funnier. The differences were subtle: Woolf changed “shrieked” to “cried” on Dickinson’s suggestion, for example, and refined the punctuation throughout. But the total effect, said Seshagiri, was like “seeing a room that’s really cluttered, and then that room gets tidied up - and all of a sudden, its inherent integrity and coherence leaps out at you.”

The revision made clear how Woolf’s project grew into something with “a much greater reach of literary possibility, for what it means to tell the story of a woman’s life,” Seshagiri said. “Because at some level, that is the guiding question throughout all of her writing: How do we tell the stories of a woman’s life? The forms we have available to us are inadequate, because the lives that women are allowed to lead are inadequate for them. So how do we rewrite some of those rules?”

“The Life of Violet” “is hugely significant and has been overlooked,” said Jane Goldman, who edited the Cambridge University Press edition of Woolf’s works. This is partly due to the fact that the earliest shapers of Woolf’s literary reputation, her husband, Leonard, and her nephew and biographer, Quentin Bell, tended to play up certain misleading stereotypes about her, Goldman continued: “not least that she was apolitical, that she was mad a lot of the time, and also that she was not a sexual person.”

“When you think about the kind of moral straitjacket that, at the turn of the 20th century, was on women - to find this intimate document is very, very moving,” Goldman said.

“The Life of Violet” contains the seeds of ideas that Woolf would go on to develop in more famous works, said Anne Fernald, an English professor at Fordham University. In addition to articulating the idea of “a cottage of one’s own” in these stories, Woolf started playing with history and fantasy in ways she would explore at more length in novels like “Orlando.” And this early fiction “restores Violet Dickinson” to a more central place in Woolf’s development, Fernald said.

Seshagiri also hopes that, in addition to their scholarly value, the stories enchant a wider audience of readers: “I don’t ever want to make the claim that this is a work on par with ‘To the Lighthouse,’” she said. “But it’s like a piece of dark chocolate. Here is something delightful and, in itself, very enjoyable, very accomplished and really surprising.”