Peter Asen, 36, drinks a liter of nonalcoholic beer in the beer garden at the Augustiner Brewery tent at Oktoberfest in Munich.

Image: Aaron Wiener/The Washington Post

Aaron Wiener

It looked like all the other beers in the sea of giant one-liter glasses at the Augustiner Brewery tent at Oktoberfest, but Peter Asen’s mug harbored a secret: His drink was nonalcoholic.

Asen, 36, isn’t a teetotaler - he’d already drained two liters of old-fashioned beer. But as the Munich local drank with friends, a bouquet of faux flowers tucked festively into his shirt collar, he alternated with the alcohol-free version.

“Water in the tent costs as much as nonalcoholic beer,” he said. “And I like beer better.”

Asen’s drink was a small sign of a big trend in Germany, a country long associated with beer, and specifically with hyper-traditional brewing. Quietly, Germany has become the world leader in the consumption of alcohol-free beer by volume, according to IWSR, a London-based firm that tracks global alcoholic beverage data.

More than half of Germans who are at least 16 - the legal drinking age - have bought nonalcoholic beer or cider, Susie Goldspink, IWSR head of No and Low Alcohol, said.

This year, for the first time, every suds-serving tent at Oktoberfest offered nonalcoholic beer as well, according to event organizers. (Last year, all but two had an alcohol-free alternative.)

An alcohol-free beer inside the Spaten Brewery tent at Oktoberfest.

Image: Aaron Wiener/The Washington Post

Nonalcoholic beer accounts for about 9 percent of both beer production and consumption in Germany, and in the coming months those figures are expected to reach double digits, said Holger Eichele, general manager of the German Brewers Association.

Germany hasn’t abandoned its commitment to beer tradition: Nonalcoholic beers conform to the country’s 500-year-old Reinheitsgebot, or purity law, which requires beer consist of just four ingredients: water, malt, hops and yeast.

But while adhering to these strict principles, the German beer industry has leaped into the vanguard to create a vast array of nonalcoholic beers that experts say compete on taste with their storied forerunners.

Unlike in the United States - where the market leader in nonalcoholic beer, Athletic Brewing, focuses solely on alcohol-free products - every major German brewer offers nonalcoholic beers, usually in several styles, providing an explosion of options for drinkers wanting to stay sober.

Nonalcoholic beer consumption in Germany has more than doubled since 2012, according to Euromonitor International, a London-based market research and data analytics firm.

“Now if you’re a major brewery, you almost can’t not have at least one nonalcoholic beer,” said Raphael Moreau, Euromonitor senior research consultant for drinks and tobacco.

Alcoholic pilsners are still the most popular beer in Germany, followed by “helles” light lagers. But nonalcoholic beer has overtaken wheat beer in third place, Eichele said, and could soon leapfrog Helles.

The high demand has surprised some breweries. Augustiner - one of Munich’s most storied and beloved breweries, dating to 1328 - introduced its alcohol-free Helles last year. Since then, it has frequently sold out in stores, leading to rationing and price hikes.

Louis Schirmer, 22, of Munich, proudly holds up three alcoholic beers at Oktoberfest.

Image: Aaron Wiener/The Washington Post

A flat start, a frothy rise

The modern German history of nonalcoholic beer traces to East Germany in the early 1970s. The Communist regime, alarmed at heavy drinking among workers in major industries, decided to commission an alcohol-free beer. It turned to a brewer from Saxony named Ulrich Wappler.

Wappler developed a process of pausing fermentation before a significant amount of alcohol had been produced. His beer debuted at the 1972 Leipzig Trade Fair as “Aubi,” short for Autofahrerbier, or car driver’s beer.

“The Aubi tasted terrible,” Wappler, now 89, conceded in an email. (Health issues prevent him from speaking.)

The first alcohol-free beers were “a sweet, malty swill,” said Eichele. By stopping fermentation early, the yeast wasn’t given a chance to digest the sugars.

Wappler said he secretly met with a professor at the University of Munich - across the Iron Curtain in West Germany - who helped him improve the taste. He also traveled to countries including North Korea, Ukraine, Belarus and Mongolia to share his expertise.

The leap into the production process now favored began with an experiment in the early 1990′s by the world’s oldest brewery. Weihenstephan, founded in 1040 by Benedictine monks, in partnership with the Technical University of Munich. Rather than stopping fermentation early, they extracted the alcohol using a vacuum distillation method.

“The approach that we and the TU took back then was simple: How can you create an alcohol-free beer that has no sugar and [few] calories, and maybe more important, tastes like beer and not like a sweet drink?” said Tobias Zollo, Weihenstephan’s head brewmaster.

At first, few people bought Weihenstephan’s nonalcoholic beer, Zollo said. “There were people in the brewery who said, ‘That’s not what we do, that’s not real beer,’” he said.

But in the past two to three years, demand has shot up, Zollo said. Now, 11 percent of the beer Weihenstephan sells is alcohol-free, a figure he expects to keep rising. (Technically, most nonalcoholic beers in Germany aren’t completely alcohol-free - they can have up to 0.5 percent alcohol, similar to some juices and ripe fruit.)

Nonalcoholic beer’s rise comes at a precarious time for German breweries. Overall beer consumption in the country has been declining for years, and brewers complain of lower profit margins as costs rise but beer prices stay flat. Some brewers have closed.

For others, alcohol-free beer has become a lifeline. The small Wiethaler brewery has operated in northern Bavaria since 1498, and has been in Andreas Dorn’s family since his grandfather bought it after World War II. The business has struggled.

Nearly 20 years ago, while his mother was in medical rehabilitation, Dorn quietly started experimenting with nonalcoholic beer. When she found out what he was doing, she thought he was crazy, she told a Bavarian broadcaster. But, she said, nonalcoholic beer now makes up one-fifth of Wiethaler’s sales and has saved the family brewery.

“I wouldn’t dramatize it that much,” Dorn said in an interview, declining to confirm sales figures. But he said: “With alcohol-free beer, our industry in general has a shot at survival again.”

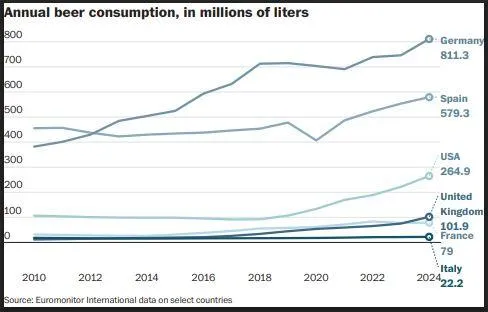

The annual beer consumption in European countries and the USA.

Image: Supplied

Beverage of champions

At last month’s Berlin Marathon, the ads were everywhere: “Erdinger alcohol-free - The sporty thirst-quencher.”

That may sound curiously like a Gatorade pitch, but the Bavarian brewery is far from alone in promoting to athletes. Many nonalcoholic German beers are labeled “isotonic,” meaning they have roughly the same concentration of electrolytes as human blood, supposedly making them better for rehydration and exercise recovery than water or sports drinks.

As far back as the 2018 Olympics, most German skiers were drinking nonalcoholic beer during training. The beer industry touts several studies showing lower rates of inflammation and infection among athletes who consumed alcohol-free beer compared with placebos.

Historically, beer gained popularity in part for its health benefits. As Dorn pointed out, in the Middle Ages, when his family’s brewery was founded, beer was considered safer than water, because the brewing process, along with the alcohol and hops, kills microbes.

Now, amid growing awareness of the adverse health effects of alcohol and sugary drinks, a younger generation is swinging back to beer - the nonalcoholic kind.

“Younger people are consuming much more consciously and much more healthily,” said Eichele, the beer association director. “Alcohol-free beer is a lifestyle drink these days.”

He added, “You can also drink 20 of them.”

The shift to alcohol-free beer has downsides for brewers. It takes longer and costs more to produce than traditional beer but is generally sold for the same price.

Germany is not the only country seeing a nonalcoholic boom. Sales in Ireland - another country known for its beer traditions - more than tripled from 2017 to 2021, according to Drinks Ireland, a trade association. Still, that was just 1.5 percent of market share, far less than in Germany.

Eichele believes Germany leads in nonalcoholic beer because it got a head start, and that other countries will catch up.

“I was recently in Qatar during Ramadan,” he said. “And I thought it was a shame that there was no zero-alcoholic beer. These are huge markets that could be tapped into.”

As rapidly as nonalcoholic beer is growing in Germany, it was still an outlier at Oktoberfest, the annual celebration, with an estimated 7 million visitors, mostly Germans.

Jenny Stader, serving the thirsty masses at the Augustiner tent, estimated that 20 percent of sales were nonalcoholic. Others put the figure far lower. On a recent evening, three servers in the Paulaner tent tried to recall if they’d sold any alcohol-free beer that day. None remembered selling a single one.

Sitting outside the Augustiner tent, Louis Shirmer, 22. a carpenter from Munich, summed up a common attitude as he nursed his fifth liter of the day: “Only idiots drink nonalcoholic beer.”